Great news on the book front: Kathryn Wysocki Gunsch, Department Head for the Arts of Africa and Oceania at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, just published her eagerly awaited research on Benin plaques as a book. As her academic publisher is not really making any promotion for it (which it rightfully deserves), I thought I gave a little feature here. The blurb reads:

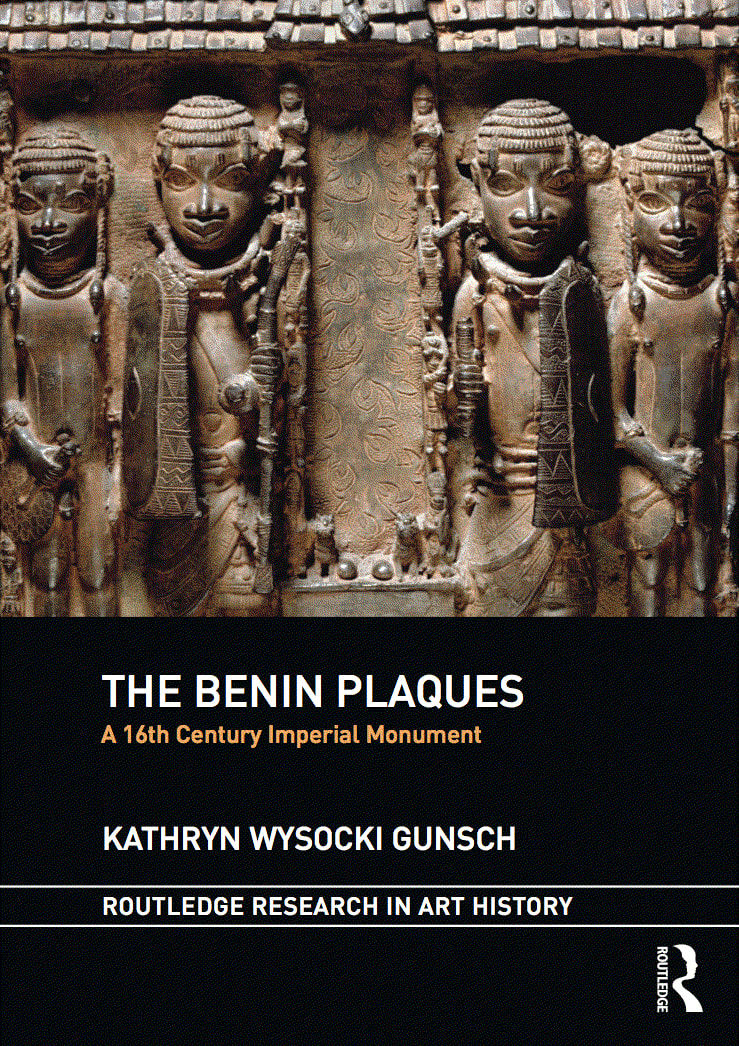

The 16th century bronze plaques from the kingdom of Benin are among the most recognized masterpieces of African art, and yet many details of their commission and installation in the palace in Benin City, Nigeria, are little understood. The Benin Plaques, A 16th Century Imperial Monumentis a detailed analysis of a corpus of nearly 850 bronze plaques that were installed in the court of the Benin kingdom at the moment of its greatest political power and geographic reach. By examining European accounts, Benin oral histories, and the physical evidence of the extant plaques, Gunsch is the first to propose an installation pattern for the series.

Gunsch spend more than four years on the subject, traveling the world to handle as many plaques as possible. If you are as obsessed as me with these, this is a must-read. I thought I’d do a small interview with her to tell us more about this research project.

What brought you to Benin plaques ?

I began studying Renaissance art history when I began my masters/PhD program at the Institute of Fine Arts, at NYU. I thought I would minor in African art history, because I had spent a lot of time in Nigeria, Kenya and Rwanda in my former career in international development. I was surprised at how anthropological the discourse in African art history was, especially compared to Renaissance art, and I realized I had more to contribute in this field, so I made African art history my main subject in my second year and never looked back. I have always loved 16th century bronzes — first in Italy and then in Nigeria — and so the Benin bronzes were a natural fit for a topic.

There’s already a lot of literature of the art of the Benin Kingdom, when did you realize you could add something to the existing scholarship?

I had a pit in my stomach when I walked into my first meeting about the project with Susan Vogel, who supervised my dissertation with Jonathan Hay. I had done a preliminary literature survey and couldn’t find the installation proposal for the plaques — I was sure I had somehow missed a major publication. When Susan said there hadn’t been any installation proposal, I knew I had something to offer. It still boggles my mind that no one has tried to reconstruct the 16th century audience hall before — but then again, it is a lot easier to do now that I can organize images of this 850+ corpus on Flickr!

What do you see as the biggest revelation in your book ?

My biggest revelation in the research was that when you look at the entire series, there are overlooked clues to dating and workshop method, as well as the original installation plan. I saw more than 640 plaques in person and another 100 by photograph, and looking at so many helped me find new insights. For example, all of the wide plaques have one of three patterns on their flanges, the small collar of brass perpendicular to the left and right sides of the plaque surface. In the book, I explain how these flange patterns are likely a signature of the head of the brass-casting guild, and that they certainly mark a progression in time. You can see how plaques with one pattern are in lower relief and show less daring use of the medium than the plaques with other patterns, a sign that the brass-casting guild is learning as it completes the commission. Looking at the reverse of the plaques, and the way the river-leaf pattern is applied to the front, I believe we have evidence for a guild production method that shrinks the dating of the corpus to less than 60 years. This is the more objective ‘new news’.

I’m curious to see what readers have to say about my more hypothetical proposal, that pairs and near-identical series can support a theory of which plaques were installed on the same pillar as each other, and why. It turns out that 36% of the known plaques have a near-identical pair. That’s not easy to achieve in lost-wax casting, where the clay mold is destroyed in the casting process. My installation proposal argues that the pairs and sets structure the corpus, giving the installation a framework within the enormous architectural space of the court. I’m trying to explain why the brass-casters would have gone to the extreme effort to make these pairs and sets, and what the Obas reigning at the time — Esigie and Orhogbua — could have achieved with this monumental commission.

Did you get to answer all the questions you had ?

No! We never get to answer all our questions, right? I am still not sure why the first set of plaques has a strict width of 30cm, and the narrow plaques are nearly all 19cm wide, but the later sets are more variable in their width. But if I had answered all my questions, what would I do next?

How was the experience of going to Benin City yourself ?

I loved visiting Benin City. I had spent a lot of time in Abuja and had visited Lagos before, but coming back to Nigeria and spending time in Benin City made me appreciate the importance of the kingdom’s art history today. This isn’t a dead subject — Oba Ewuare II reigns over a thriving court, with all the politics that entails. Seeing his father, Oba Erediauwa, during a title ceremony really brought that home. Thinking about Oba Erediauwa’s commissions in the Ring Road at the city center helped me focus on what kings achieve with the art works they sponsor. I didn’t have an audience with the Oba, but his brothers and other high court officials were gracious and patient with my questions, as was the then-new head of the brass-casting guild, Kingsley Inneh, and his uncle Daniel Inneh. I wish I could go back more often.

What are your future plans ? Is there already another book/project in the pipeline ?

I’m currently working on a theory that the altar figures are paired, just as the plaques are — and I mean paired to the centimeter, not just having similar iconography. It seems that triadic symmetry is a main feature of Benin aesthetics, and I wonder what we can learn about the heads and the altar figures if we apply that idea. I’m not sure it will be enough material for a book, but we’ll see!

I’m looking forward to that; thanks for the interview Kathryn.

If you want to learn more, you have to buy the book; you can can order it here !