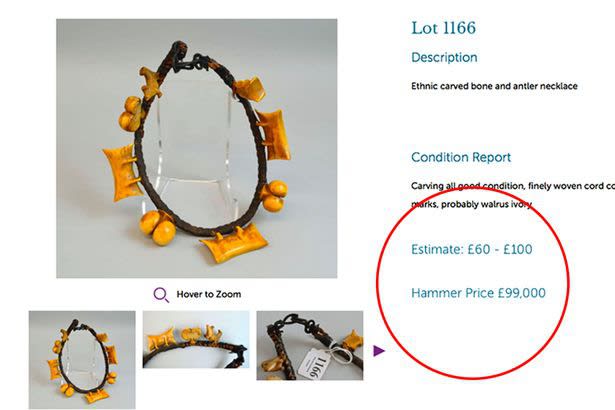

Austral Islands necklaces are among the rarest and most sought after of all Polynesian artifacts. It was thus no surprise that when a newly discovered example popped up in a small auction in the UK, listed as an ‘ethnic carved bone and antler necklace’ and with an estimate of only £60-100, it was sold for £125,000 (including premium).

The lucky seller runs a house clearance firm and found the item among the contents of an empty property he had been tasked to clear. He had no idea of its value and arrived at a jumble sale with a view of selling it for £15. But he had a change of heart at the last moment and decided to pop across the road to an auction house for experts there to have a look at. They believed it to be an 18th century ethnic carved bone and antler necklace and told him it might be worth between £60 and £100. However, Auctioneer Chris Ewbank started to suspect he underestimated the item in the days leading up to the sale when potential buyers booked up phone lines and left preliminary bids. And when it went under the hammer on 2 December at Ewbank’s Auctions of Surrey (UK), three bidders forced the bidding up to a staggering £99,000. With fees added on the Paris-based winning bidder will pay £125,000 for it.

Mr Ewbank reacted in this interview: “It is what we in the business call a sleeper, it came out of nowhere. It can make the auctioneer look slightly silly because they failed to spot a gem. There’s no point in trying to hide the fact that we got this one wrong.” In 2010, Sotheby’s sold a similar necklace from the Niagara Falls Museum for £ 200,000. Julien Harding wrote in the catalogue note:

The iconic status of these ornaments is enhanced by a certain mystery which has surrounded their place of origin. In establishing this it will be helpful to begin with the “testicle” pendants which are known in a variety of sizes and materials (ivory, bone, wood). In the official account of Captain Cook’s last voyage we find a description of the natives of Atiu, one of the southern Cook Islands: “Some, who were of a superior class, and also the Chiefs, had two little balls, with a common base, made from the bone of some animal, which hung round the neck, with a great many folds of small cord” (Cook, 1784).

William Wyatt Gill of the London Missionary Society noted that such objects were worn as ear ornaments by the chiefs of Mangaia, the southernmost of the Cook Islands (Gill,1894).

Later, E.L.Gruning, who lived in the Cook Islands from 1905 to 1914, carried out an exploration of Atiu during which he had himself lowered into a cave of unknown depth at the end of a makeshift liana rope. His courage was rewarded by the discovery of human skeletons and two “phallic ornaments”, one suspended from braided human hair, in the manner of a Hawaiian lei niho palaoa. He notes that these ornaments “are reputed to have been worn only by champion warriors of the island, who had the right of possessing any woman, married or single, while wearing one” (Gruning, 1937). The term “phallic”, used by several authors to describe these pendants, is of course a mistake. They may well represent testicles but certainly not a phallus.

It is thus certain that individual testicle pendants were worn as chiefly ornaments in at least two of the Cook Islands in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Very possibly they were similarly used in the neighbouring Austral Islands since there was canoe contact, both deliberate and accidental, between the island groups.

If we now turn to the composite necklaces themselves we find the evidence of origin much less clear, no doubt because early records for the Austral Islands are extremely sparse. In his monumental Album (1890) Edge-Partington published a fine example, attributing it to Mangaia (plate17, no.2). Te Rangi Hiroa (Peter Buck, 1944) gave a detailed account based on the ten necklaces known to him and held in various institutions: British Museum (2), Cambridge University Museum, England (2), Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh (1), Boulogne Museum (1), Peabody Museum, Cambridge, Massachusetts (1) and the Oldman Collection (3). He also attributes these necklaces to Mangaia, but suggests a close connection with Rurutu in the Austral group. Significantly, Buck states that the pig was unknown in Mangaia but was present in Rurutu (ibid.).

More recently Roger Duff pointed firmly to the Australs as the origin for these necklaces on the basis of old missionary attributions for three examples not known to Buck. Two, now in the Canterbury Museum, New Zealand, were previously in the Wisbech Museum, England, where they were described as “Necklaces from Rurutu, Austral Islands. Composed of the fibres of cocoanut, human hair and bones; worn as a memorial of friendship. Rev. Wm. Ellis 26.8.1841”. Duff notes that a third necklace, in the Saffron Walden Museum, England, is also attributed to the Australs and specifically to the island of Tupua’i (Duff, 1969).

A persuasive argument in favour of the Austral Islands derives from comparative morphology. The famous figure of A’a in the British Museum (Harding, 1994) is certainly from the Australs – it was given up to John Williams of the London Missionary Society in 1821 by a party of Rurutu islanders. The small figures (“demigods”) carved on this sculpture closely resemble those on a whalebone bowl of typical Australs form (Oldman collection no. 476, now in the Auckland Museum). This bowl has a handle in the form of two pig figures identical in style to the one on the present necklace.

Thus, on the available evidence, we can safely attribute these beautiful necklaces to the Austral Islands, those specks of land to the south of Tahiti which produced some of the finest art of the Pacific. The Australs culture, briefly glimpsed by Captain Cook in 1769 and again in 1777, was more or less intact when Fletcher Christian and the other Bounty mutineers arrived there in 1787. Missionary influence and introduced diseases effectively destroyed the old way of life and today this is merely a remote corner of French Polynesia with a total population of 6500 and virtually no trace of the original culture. The survival of a few Australs masterpieces, such as the necklace offered here, is of the greatest importance. These objects are silent witnesses to a tradition of superb craftsmanship which has disappeared for ever.

The necklace may be compared with three examples in the Oldman collection (illustrated in Oldman, 1943, plate 21, nos. 477, 478, 479) and with three in the Hooper collection (illustrated in Phelps, 1976, plate 83, nos. 654, 655, 656). Understandably, very few Australs necklaces have ever appeared at auction. One of the Hooper examples (no.654) was sold at Christie’s, London, June 17, 1980. After many years in the De Menil collection this reappeared at Sotheby’s, New York, auction on November 22, 1998. Another Hooper necklace (no. 656, the Edge-Partington example previously mentioned) was sold by Christie’s, London, July 3, 1990.