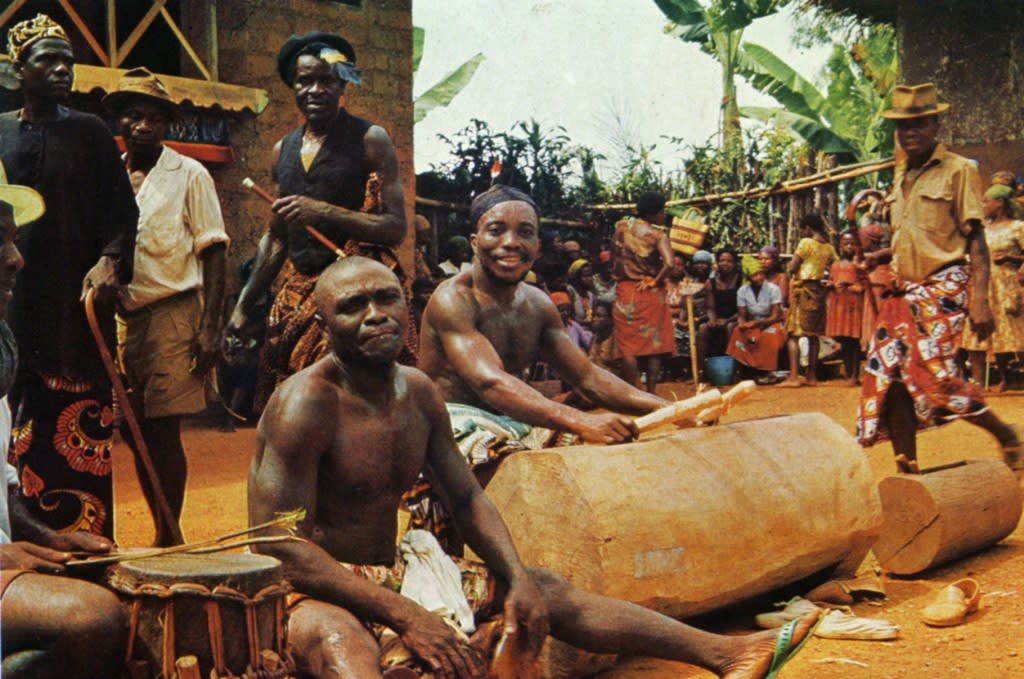

Since the number of traditional African sculptors of who we know the identity is so limited, it is always exciting to discover a name and a face to attach to a previously anonymous mask or statue. I found this wonderful description of the Bangwa artist Atem in Robert Brain and Adam Pollock’s Bangwa Funerary Sculpture (London, 1971).

At the time of their research the best known of the Bangwa carvers was Atem, pictured above. He lead a free-and-easy life: his prowess with the adze and his devotion to pleasure were equally renowned. When not working Atem lived for the moment. Once a mask or drum had been completed and the money handed over, the money was mostly invested in drink, which he shared with his crowds of friends. Unusually for a Bangwa, Atem was uninterested in other material comforts. He worked in a small decrepit hut kilometers away from the Bangwa centres. A visit to him and his young apprentices involved a steep, muddy trek to a forested mountain slope in Upper Bangwa. in spite of his many opportunities for wealth, he had only a single wife. This was startling to a Bangwa, since a man’s success was usually determined by the number of wives housed in his compound. Atem carved more and more for wealthier patrons outside Bangwa. He carved masks for Banyang societies and royal stools for neighboring Bamileke chiefs. He was even sought after in the cultural foyers in the French dominated towns of Yaounde and Douala, and he had made a stool for the wife of the president of Cameroon. Although he traveled widely (‘to drink’, he said), he returned home to work. The picture below shows a Bangwa night society mask carved by Atem in 1967.

Atem preferred to carve masks associated with ‘jujus’ which had been recently imported from the forest areas; these were the dance societies which were most popular with Bangwa youth at that time. Atem was commissioned by the society, the members of which contributed money to pay for a mask which may cost anything from £3 to £15. These were usually janus-headed, horned masks, painted in brightly colored European hues. As shown below, they were lively, extrovert and amusing, a far cry from the expressionistic night masks or the serene memorial figures of the old artists.

Atem also carved drums, vast slit-gong drums which he worked in situ in the forest, often simply following the shape of the tree trunk from which they were cut; they were then hauled complete to the owner’s compound. Other drums were elaborately decorated at the ends; one for example having the portrait of a chief and his process at either end. Atem was also an expert musician as well: the ‘sound’ of the drum for him was as important as its appearance. Not surprising, he was a virtuoso on the drums and a fine dancer as well.

In December 2014, Christie’s Paris offered a mask that in all likelihood also was made by Atem (lot 23). It clearly shows the same typical characteristics (note the overhanging brows, swollen cheeks and specific shape of the mouth). In the catalogue we read that this mask was collected in 1950 – 17 years before the one illustrated above. Estimated € 30-50K, and without Atem being listed as its sculptor, it failed to sell – probably its half eaten state had something to do with that.

Brain & Pollock conclude their description of Atem by stating that he was a typical example of the individualistic carver working on his own. Bangwa society gave free rein to individuals and even by their standards the sculptors were allowed great unconventionality. Famous carvers of the past were remembered as ‘bohemians’ – wits and personalities who refused to conform to Bangwa norms. In their desire for nonconformity, Bangwa sculptors like him thus had something in common with most of todays contemporary artists.