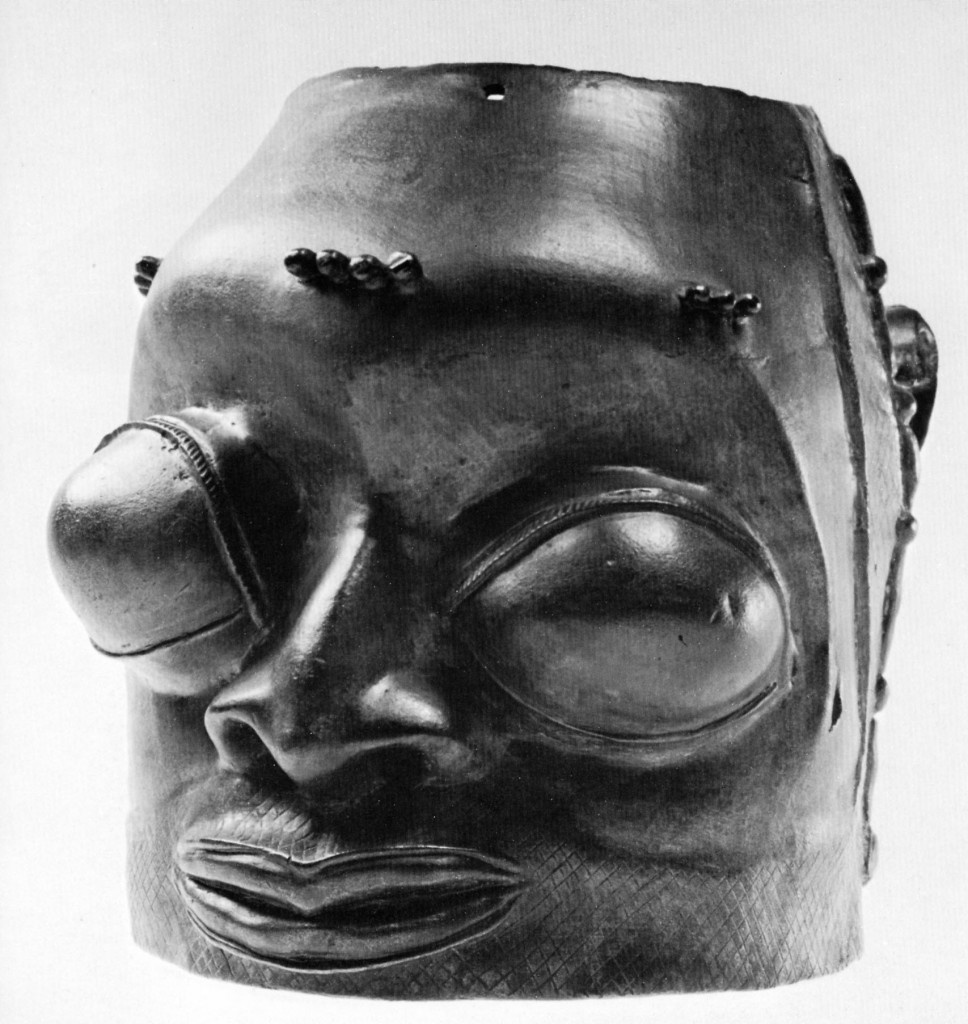

In my personal top 10 of African art, is this bronze head from the George Ortiz collection. I first saw it in Paris in 2010 during the exhibition about the film by Alain Resnais and Chris Marker, Les statues meurent aussi ; the force it radiated was incredible. Perhaps, on a subconscious level, there’s also a degree of identification since I was nicknamed ‘bulgy eyes’ as a child :)

The George Ortiz collection can be consulted online. The main focus is ancient Greek art, but there are some splendid examples of African and Oceanic art too.

This head was found during the British Benin punitive expedition in February 1897 in Benin City. Made in the Yoruba tradition: though possibly in Ijebu it could very well have been made by a Yoruba artist in Benin City and it is even conceivable that “Bulgy Eyes” could be a late Ife work. In art it would seem by observation of their respective works that the Yoruba must have had strong artistic ties and a “close on-going relationship with Benin”.

This bronze head bears tribal markings above the eyes and on the forehead. On either side of the Bini-like ears hang coral pendants with small crotals or nuts at their end. On the back of the head is something of indeterminate nature, either a rattle, bell or large nut. The hair and beard represented by cross-hatching which extends also above the upper lip.

With its immense bulging eyes and wide, hooked nose with flat nostrils, this head is one of the most extraordinary expressions of African art. We see in it the essence of Nature’s savagery and the “bulging eyes represent an extreme of the Oshugbo convention suggesting spiritual force and presence.”

It may have been placed on a royal ancestral altar, found in what Pitt Rivers called “Ju-Ju” houses and would have been used in spirit cult. It could have been surmounted with a headdress, as Drewal suggests. It is unlikely that it served to hold an elephant tusk as some of the tall and heavy Benin heads of later periods did. By its mystical strength, we feel that this unique head is a universal work of art.

An excerpt from a short interview with George Ortiz:

How does ethnography fit this collection?

Because some of it is very powerful, very pure or very beautiful sculpture, or both, often with a strong inner content. I have always liked African sculpture when it is genuine, which means unadulterated by European contact. And the Africans as no other peoples have been able to capture and express the savagery of nature in some of their sculptures, for nature is not burdened with considerations of morality or justice, it just is. See for example the Nok head, with its powerful psychic content, and “Bulgy eyes”, with its mystical strength.