On the occasion of its forthcoming exhibition Unsettled, Duende Art Projects is proud to have identIfied a previous anonymous Wurkun artist.

The present kundul statue counts among one of the best of its type. Kundul are one of the most radically abstract figurative conceptions found in the middle Benue River Valley, with large heads and elongated necks surmounting cylindrical torsos. This figure reduces the human form to a bare minimum of basic columnar shapes. The arms in raised relief are sculpted as a closed oval shape, framing a protruding umbilicus. The head is also highly stylized, with the ears, nose, and mouth portrayed as a set of sharply angular forms. Wurkun men once filed their teeth, represented here by incisions on the mouth. As part of the kundul’s ritual activation it was anointed with water and red ocher and ‘fed’ a grain-based local beer, resulting in a deep multi-layered patina. The present example shows remarkable signs of old age and long traditional use as a shrine object. The statue is standing on an iron spike hammered into the base that secured the sculpture to the ground and protected the wood from termites. This fine example shares the stylistic features common to male kundul. According to Joerg Adelbergers (Berns, Fardon and Kasfir, "Central Nigeria Unmasked: Arts of the Benue River Valley", 2011, pp. 425-432), who undertook extensive field research on the Wurkun, male gender is identified, as in this figure, by the high transverse crest atop the head, which depicts the dance helmets with side flaps that men wore on ceremonial occasions.

Kundul are produced by carvers who are often blacksmiths – as can be anticipated given the presence of the iron spikes in their base. Typically, they are made on the directive of a priest who will tell a person seeking his help to procure such a sculpture for further use in ritual treatment. These

anthropomorphic sculptures are used in a variety of rituals, usually concerned with healing and well-being. For instance, they may be commissioned after a breech birth has taken place or when someone has fallen ill, or they may serve as a protective device when a hunter is haunted by the spirit of an animal he has killed. A kundul gains its powers only after appropriate rituals and sacrifices have been made to give it life and power. For instance, a person suffering from disease will visit a healer who may instruct him to procure a pair of these figures as a component of the treatment. The kundul will be sprinkled with the blood of a sacrificed chicken and with millet beer. A pot may be placed beside the kundul to receive regular beer offerings. Offerings should be repeated annually after harvest, when the first fruits of the new crop are sacrificed to the figures. At this time, the kundul are brought out of the house and washed with a solution of water and brown or red clay. Afterward they are polished with oil made from guna seeds (Cucumis melo), and they are fed beer and porridge made from the new millet. The present statue shows clear signs of such a prolonged ritual use, with clear signs of the red clay solution to the ears.

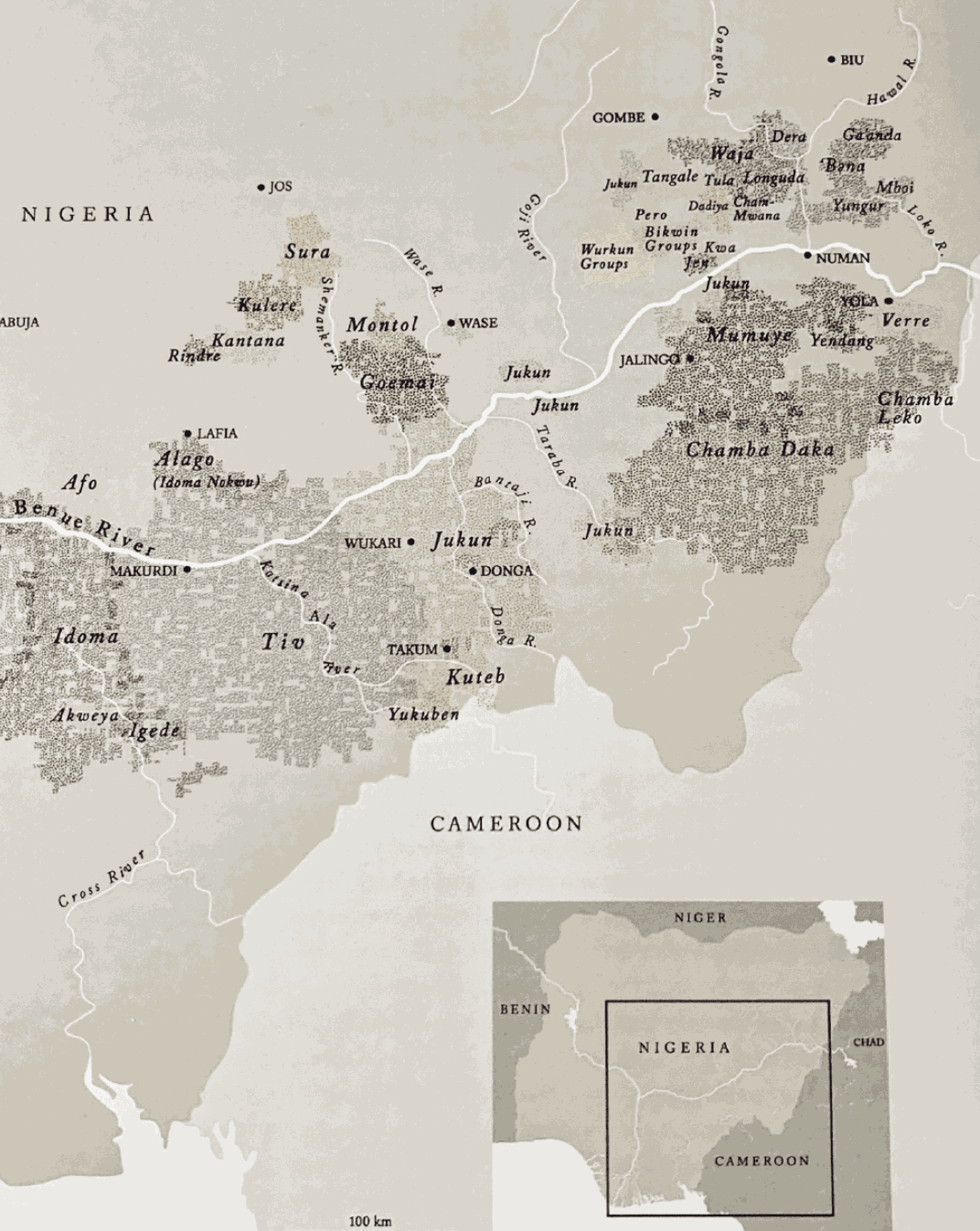

The cluster of groups living in the western Muri Mountains is known as the ‘Wurkun”. This common designation is Jukun in origin and simply means ‘people of the hills”. Its use predates colonialism and was first recorded in 1855 by members of the Niger-Benue Expedition. Like other such terms originated by outsiders, it came to be accepted by many to whom it was applied. The Piya, Kulung, Kwanci, and Kode, although speakers of largely distinct languages, identify themselves as Wurkun. However, although the differences, there is a clear indication of historical ties and local migrations. Hence, despite its external origin and the diversity of the languages used, this common “Wurkun” identity does have some historic basis in shared cultural features and social interactions.

Map source: Berns (Marla C.), Fardon (Richard), Littlefield Kasfir (Sidney) (ed.), "Central Nigeria Unmasked: Arts of the Benue River Valley", Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, 2011, p. 22.

Research and photographic documentation show that kundul were widely used prior to the 1970s. The American scholar Arnold Rubin undertook extensive fieldwork in the region in the 1960s and photographed a group of such columnar figures in a compound in Lunga, a Piya village in the northwestern part of the Muri Mountains on January 10th, 1966. Central on this picture we find a kundul pair (statues no. 5 and 6 from the left) that are clearly sculpted by the same artist who created the present statue. The third statue from the right is another statue by the same master carver, hence dubbed “The Master of Lunga”.

Berns (Marla C.), Fardon (Richard), Littlefield Kasfir (Sidney) (ed.), "Central Nigeria Unmasked: Arts of the Benue River Valley", Fowler Museum at UCLA, Los Angeles, 2011, p. 420, fig. 13.4-5 (Rubin Archive, Fowler Museum at UCLA, no. 1624). The ceramic pots in front were used for offerings.

Provenance: Pace Primitive, New York City, USA, 1976. William Brill Collection, New York, USA. Peter Wengraf, San Francisco, CA, USA. Myron Kunin Collection, Minneapolis, MN, USA. By decent in the family, 2014. Sotheby's, New York, "In Pursuit of beauty: The Myron Kunin Collection of African Art", 11 November 2014. Lot 65. Private Collection, Leuven, Belgium, 2014-2021. Duende Art Projects, Antwerp, Belgium, 2021.

We are very proud to show this stunning Wurkun kundul statue at our forthcoming exhibition UNSETTLED, opening next week in Antwerp. We hope to see you there!