The nucleus of our current Sweet Dreams exhibition is a carefully curated selection of nine Shona headrests from Zimbabwe. I had been discreetly collecting them over the past year and was happy to present them to the public during my first participation of the renowned Paris art fair Parcours des Mondes. Shona headrests have long been cherished by collectors; it is easy to admire their design and patina, yet the many symbolic references they contain add a most fascinating layer to their appeal. As the educational mission of Duende Art Projects is one of its core values, I thought it would be nice to share some more information about their history, usage and symbolism. The below text is paraphrased from William J. Dewey’s 1993 publication “Sleeping Beauties”, which includes a summary of the author’s Ph. D. thesis on the subject.

THE HISTORY AND USE OF HEADRESTS BY THE SHONA

Within the wondrous world of African Art, the Shona people are especially known for their exquisite headrests. Although no documentation exists about the age of the headrest tradition in the region, gold sheeting has been recovered from the twelfth century site of Mapungubwe along the Limpopo River. This ornamentation discovered in a grave is believed to have adorned a wooden headrest, long ago disintegrated. The practice of sheathing headrests with metal may have continued during the times of Great Zimbabwe and the successor states in the region during the thirteenth through seventeenth centuries. Important individuals appear to have been buried ‘sleeping’ on their headrest. While the wooden object decayed, the gold plating survived. Unfortunately, most of the excavated gold was molten and we are left to speculate about the original shape of these headrest.

"The Horns", anonymous Shona artist, wood, 229 g, 14 x 21 x 7 cm. The only known Shona headrest featuring two pairs of antelope horns; they might have stimulated the owner (most likely a hunter) to dream about next day's chase. Click on the image to discover more views.

Using headrests to protect elaborate coiffures has had a long history in the area, as described by the earliest Western travelers in the region. Thomas Baines, who traveled in the Shona area in 1870 wrote that ‘to keep the well-oiled hair locks from being soiled by dust, every man carries with him a neck pillow, like a little stool, which suffers not the head to come within eight or ten inches of the ground’. J.T. Bent, who was in the Shona areas in 1891, noted that ‘the Shona sleep with their neck resting on a wooden pillow, curiously carved; for they are accustomed to decorate their hair so fantastically with tufts ornamentally arranged and tied up with beads that they afraid of destroying the effect, and hence use these pillows’. The headrests were kept in the rafters of their owners’ huts. Lucy Jacques-Rosset has commented about headrests of the Tsonga (southeastern neighbors of the Shona) that ‘these head-rests are used almost exclusively by the old natives who, when dawn has come, place them on a string, with great care, in a special place of their roof, where the smoke, mixed with the fat of their hair, gives this household implement a magnificent mellowed patina’. The same could equally well have been said of Shona headrests.

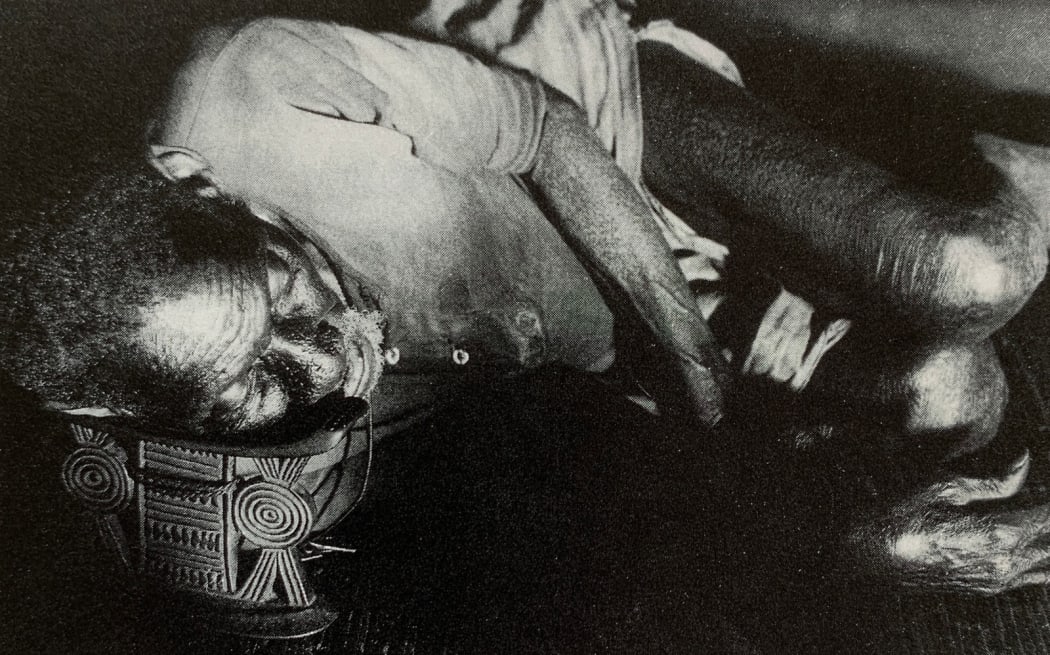

"Loved & Repaired", anonymous Shona artist, wood, 301 g, 15 x 19 x 7 cm. It is said that headrests were often intentionally broken after the death of their owner - so that no one else could use them as pillow again. This example shows signs of such a break and has been lovingly repaired with copper wirework so that it could be kept as a heirloom in the family. Click the image to explore some detail views of the meticulously made knots of the wirework.

Headrests were only used by adult men. Several sources informed William Dewey that a man with several wives would place his headrest by the hut of the wife he was going to sleep with that night. This practice was confirmed to Dewey one time by the grandmother of a sculptor: “if you saw the headrest you would know that you were going to have a visitor that night”. In contemporary society the utilitarian aspect of headrests has nearly ceased and it has become very difficult to find any headrests, much less someone who still uses them. Instead, they have taken on the role of family heirloom. As headrests became embedded with sweat and body fat, they became more personalized. They became so much part of the owner that on his death the headrest was in some instances buried together with him and other personal items. If they were not buried with their original owner, such personal items were distributed to relatives at an inheritance ceremony (known as nhaka among the Shona) after their death. Headrests could only be inherited by a male relative, preferably the brother or the son of the deceased. Among the neighboring Tsonga, headrests were preserved and kept as mhamba. H.A. Junod, the Swiss missionary who studied the Tsonga in the first decades of the twentieth century, defined mhamba as ‘any object which is used to establish a bond between the gods and their worshippers’. A mhamba was a kind of communicating vehicle through which an ancestor could be contacted. Deceased relatives stayed present and approachable through one of their most personal belongings, their wooden headrest. Many headrests in such a way became a sort of ancestral relics. Shona spirit mediums also are known to have used headrests as one of the authenticating symbols of their position and used to facilitate having dreams about the ancestors. Dreams were believed to be an important vehicle of communication with one’s ancestors and frequently acted upon.

VISUAL MOTIFS OF SHONA HEADRESTS

The standard Shona headrest usually adheres to the following parameters. The upper platform has no appendages and is decorated on the upturned ends of the platform with a chip-carved series of either parallel lines, diamonds, or a zig-zag line. The top surface of the platform can feature sets of triangles carved into it. The triangles usually are composed of smaller triangles within a larger one with the apexes pointing toward each other. The base is figure-eight shaped in plan, and gently tapers inward toward the central support. It has a downward-pointing V-shaped protrusions bisecting each side in the middle. The central support is composed of pairs of upward- and downward-pointing V-shapes separated by two or more circular shapes. These Vs have a series of two to three lines parallel to the Vs carved in them and the circles have two to four concentric circles carved within them. The centers of the circles can have various geometric designs in them, dots, horizontal lines, diagonal crosses or a pair of diamonds. The triangular spaces between the branches of the Vs and the central circular motifs are cut more deeply than the surrounding areas or are cut right through. Sometimes the circular motifs about each other and in the others they are separated by either a horizontal or vertical band filled with zig-zag lines, diagonal crosses or diamonds.

"Triangles Galore", anonymous Shona artist, wood, 126 g, 12 x 13 x 4 cm. Six triangles composed of little triangles mirrored common female scarification patterns. After a good night's sleep, the man who once owned this headrest would wake up with these motifs imprinted in his cheek to the amusement of his female neighbors.

Two key concepts are important when analyzing the visual language of Shona headrests: cicatrization motifs (nyora) and the characterizing circle motif representing conus shell ornaments (ndoro). Nyora, the word used for the incised surface decorations on these headrests, is also commonly used for human cicatrization. While the practice now has virtually disappeared, nyora were once put on women at puberty. This tradition had both public and private aspects. They served as a marker of ethnic identity but also as an enhancement of beauty to attract the opposite sex. While the motifs on the headrest carry the same name, the association with scarification is more metaphorical (both are ‘cut’ and meant to ‘beautify’) than literal (where the motifs would actually correspond). A Shona carver informed the scholar William J. Dewey that sleeping on a headrest would cause a man to have the incised scarification featured on the upper platform impressed and transformed to his own face. This would cause considerable amusement when women saw it as only they had this type of body scarification among the Shona.

"Madame", anonymous Shona artist, wood, 203 g, 14 x 16 x 6 cm. Through a chance encounter during Parcours des Mondes we discovered the identity of the Madame who once consigned this beautiful headrest at auction - click the image to discover the full provenance.

Ndoro are the concentric circle motifs characteristically featured on the middle section of Shona headrests. They recall conus shell prestige ornaments once reserved for great hunters that were worn on the forehead or tied around the neck. They are said to be incorporated on headrests to please the shave or ancestral spirits and to insure the hunt would be successful. These disks functioned both as a symbol of authority and as a valuable item that could be used as currency. Such conus shell disks circulated widely as media of exchange in Africa and cut from shells such as the Leopard Cone, Betuline Cone and Prometheus Cone. In the mid-nineteenth century, the British explorer and missionary Dr. David Livingstone reported that two cone shell disks could purchase a slave, while five bought an elephant’s ivory tusk. At some point the Portuguese began to mass-produce porcelain copies of the natural conus shell disks for trade, which still continue to circulate in the region. While the real conus shell ornaments were associated with leadership, the representation of these prestige emblems in wooden headrest was apparently not so restricted because most men owned headrests. The inclusion of the ndoro motif on the headrests must have denoted that the status of the man as head of the household and family unknit was also of considerable importance.

"The Owl", anonymous Shona artist, wood, 148 g, 11 x 14 x 5 cm. Do you see the owl? We do, but the Shona owner would have seen two conus disk shells.

A third recurring visual element in Shona headrests is the small V-shape that bisects the 8-shaped base and refers to the female sexual organs. The fact that the female pubic area and female type scarification are so prominently and consistently portrayed on Shona headrests suggest they must have been, at least in part, conceived of as being symbolic of the female gender. Not just any female, but one who had reached puberty, had had the cicatrix cut on her body and thus could be a bride and bear children. This is reinforced by the fact that it were mature men who slept with the headrest and used them to indicate who their sleeping partners would be. That Shona men in a patrilineal society would so regularly use a female symbol must be tied to the fact that they practice exogamy (must marry someone outside of their own clan), and are depend on women of other lineages to loan their fertility to their own lineages in order to ensure continuity and growth. The headrests therefor visually acknowledge the importance of women and more specifically wives in what may seem to be a male dominated society. While Shona headrest seem decidedly female in gender, they were nonetheless exclusively used by men.

"The Three Graces", anonymous Shona artist, wood, 247 g, 15 x 16 x 6 cm

"Six Circles", anonymous Shona artist, wood, 270 g, 17 x 19 x 6 cm

"The Japanese Garden", anonymous Shona artist, wood, 327 g, 15 x 18 x 6 cm