Lake Sentani Tapa Barkcloth, Maro. 115 x 170

While Duende Art Projects’ focus is art from the African continent, we were delighted to present four Melanesian masterpieces as part of the Van Strien Collection during the PAN art fair in Amsterdam. We are so in love with this important Lake Sentani tapa, I thought to tell you a bit more about it. It's never been published before and on view for the very first time this week in Amsterdam. It hadn't been on the art market for 50 years and it's a major rediscovery.

Maro is the local name for painted barkcloths from the Lake Sentani area of northwestern New Guinea, today the Indonesian province of Papua. According to the accounts of European explorers, who collected them up to the mid-20th century, maro were made and painted by women and worn as loincloths by married women and initiated girls only. This maro would probably have been worn wound around the waist, encircled by a belt. Only married women wore such barkcloth skirts. Such cloths thus marked the passage to a married state and transition to adulthood.

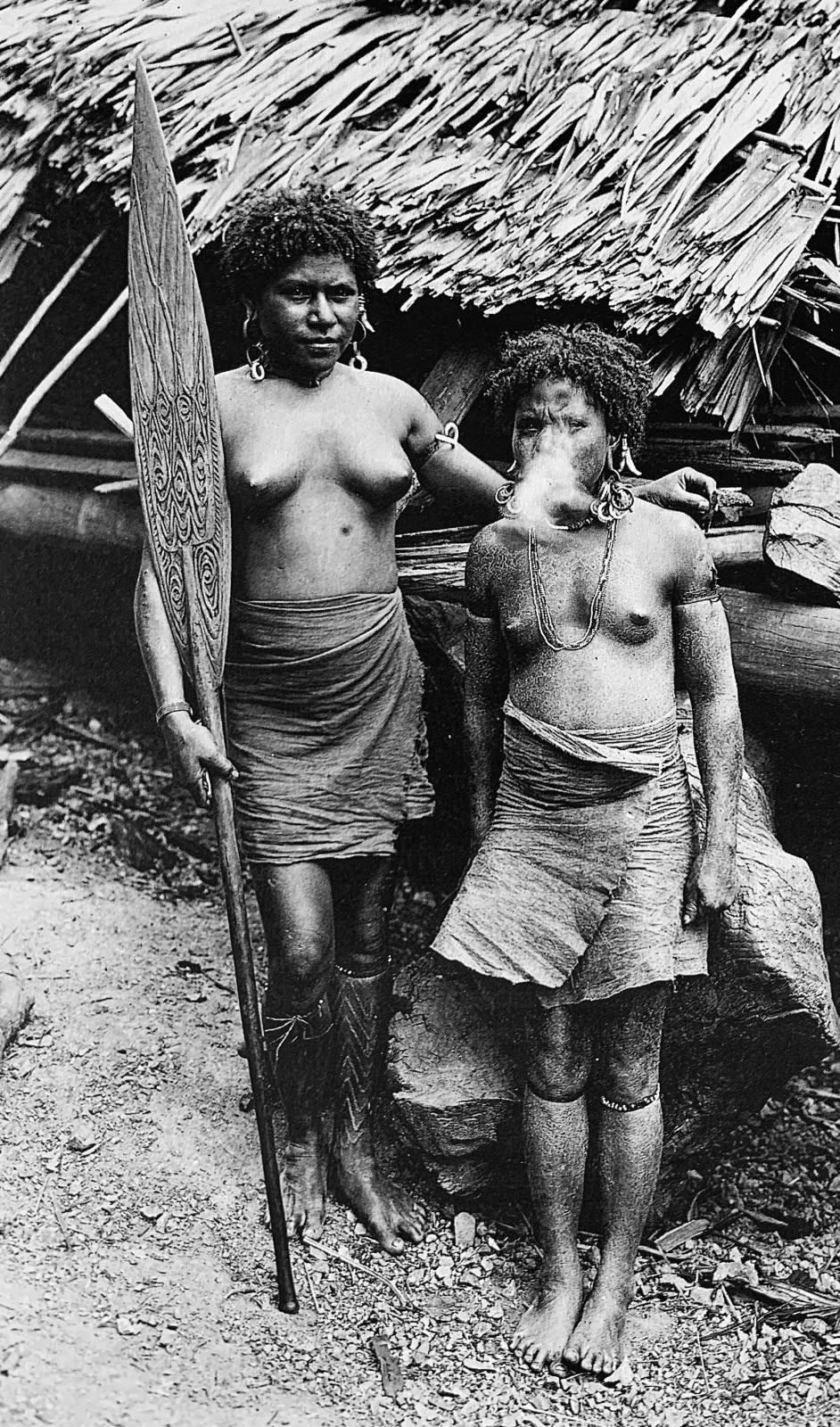

Two young women dressed in plain, undecorated maro. Note how the designs on the wooden paddle resemble the motif on the right of the Van Strien maro. Photograph by P. Wirz, 1926.

Widows wore a barkcloth cape as a sign of mourning, and the dead were wrapped in barkcloth for burial. Maro were sometimes also displayed next to graves.

Grave in the village of Siboiboi and next to it, on display, a maro. Photography by P. Wirz, 1926.

By the late 1920s the use of maro as a garment had diminished in New Guinea, since most of the barkcloth had been replaced by Western attire. The style of decoration on maro collected from this time up to the Second World War is somewhat different, and it is these figurative designs that were embraced by western artists. Instead of the pattern-like spiral designs that can be found on the early maro, there are now vivid representations of creatures resembling fish, reptiles, spirits, totems or abstract symbols. These are surrounded by scenery composed of mysterious plants, celestial motifs and otherworldly objects. The decoration on maro were called homo by the people of the Lake Sentani region. This can be translated as ‘writing’ which gives information about the village, family, clan, and owner of the maro. These homo designs were passed on from generation to generation and have a totemic or mythological origin. Some of them referred to animals that were considered to be relatives of humans. They served as clan symbols, and it was forbidden for members of those specific clans to kill and eat them. Nowadays maro from the 1920s and 1930s are rare and very much sought after by collectors and museums. The tapa from the Van Strien Collection hadn’t been on the art market since 50 years and presents an important rediscovery.

Maro donated in 1931 to the Wereldmuseum by N. Halie, government officer in Hollandia, 1926-1930 (inv. 666_320). Dimensions: 64x37 cm. Notice the similar celestial elements throughout the maro.

The very fluid painting features a large central spirit figure with seven subsidiary motifs. The overall composition is lively and vigorous, handpainted on bark cloth using charcoal and an ochre-colored pigment. The central spirit figure is depicted with eight antennae sprouting above its eyes and is looking directly at the viewer. Four eyelashes are painted on the outer side of the eyes. The spirit has a leaf-like shaped body and small limbs. Two inverted red arrow-shapes continue in a double tail. Above the captivating spirit figure, we find two celestial elements – very similar motifs can be discovered on a beautiful maro in the collection of the Dutch Museum of World Cultures, donated in 1931 by N. Halie (inv. 666-320). On the left side of the painting, there’s an abstract composition which resembles a yipwon hook figure which typically consists of a series of opposed, concentric hooks depicting the ribs, rotated ninety degrees from their normal orientation and surrounding a central element representing the heart. We haven’t been able to discover another maro containing a similar iconographic element, while it can be found on the bottom of archaic wooden bowls of the Lake Sentani Region. Underneath the central spirit figure, there’s a smaller insect-like creature, while to its left we find a bigger abstract spirit in a composition which would fit nicely in the visual language of the surrealist painter Wilfredo Lam. In the lower left corner two fishes seem to share a kiss, their heads meeting at the tip.

Detail Lake Sentani Tapa Barkcloth, Maro. Bark, 115 x 170

Maro played an important role at several influential exhibitions in Paris and New York in the late twenties and the early thirties of the last century at the time of the golden age of surrealism. Maro resembled the art of the modernist avant-garde and appeared to show the same type of abstractions as could be seen in the work of surrealist artists. In the early 20th century mindset maro were made created by anonymous artist and seemed to echo stories of a culture that was still close to the origins of the human race. Maro were paintings that showed an abstraction of forms and lines that seemed to echo the dreams, myths, magic and visual metaphors of a far-away, almost extinct culture. The surrealists were fascinated by Oceanic art in general and by marospecifically. The concept of maro paintings fitted in seamlessly with surrealist concepts. André Breton, who had assumed leadership of the movement, had a large collection of Oceanic art. Henri Matisse, Joan Miro and Max Ernst are all known to have had maro in their collections. This ‘dream world of spirits’ had a large influence on their own creativity. The maro had everything in common with those western works in which, by using a whole vocabulary of signs, the artists manipulated reality and gave expression to their conception of the world with a cosmogony peculiarly their own.

L’étoile du matin, Joan Miró, 1940, gouache, huile et pastel sur papier, 38 × 46 cm, fondation Joan Miró, Barcelone. Donation de Pilar Juncosa de Miró.

Making and decorating tapa or barkcloth is a practice that can be found all over the islands of the Pacific Ocean. To manufacture tapa, the inner bark from a ficus or paper mulberry tree is removed, dried in the sun, then soaked in water and hammered on a flat surface cause the fibres to spread out. The sustained beating of the bark creates strips of cloth of more-or-less even thickness. These strips are beaten together to form a large sheet, the edges of where are trimmed. The decorations are applied with several colors: white, made from lime; red, made from reddish stone; and black, made from soot or charcoal. The pigments are mixed with tree resin and water. The present maro is the only known example with fringes at the bottom and can be considered one of the masterpieces of the genre.

René Buthaud (1886-1986)

It was once owned by René Buthaud, one of the most important ceramicists of the Art Deco period in France. Trained in drawing and etching at the École de Beaux Arts in Paris, Buthaud was later a recipient of the prestigious Prix de Rome. His training as a classical draughtsman no doubt contributed to his pre-occupation with the beauty of the female form, and indeed the female nude was a frequent subject of the painted designs of his stylishly modern ceramics. Consistent with the taste of the period, Buthaud took an interest in African and Oceanic Art, not only for its distant allure, but also and more importantly for the simplified elegance of its forms. He developed a notable collection of non-Western, acquiring works in the port of Bordeaux, the adopted city he called home from the end of the First World War. The Antwerp-based gentleman-dealer Lucien Van de Velde would buy the maro from Buthaud and sold it to Kees van Strien in the 1970s. This early purchase would become one of the masterpieces in his collection.