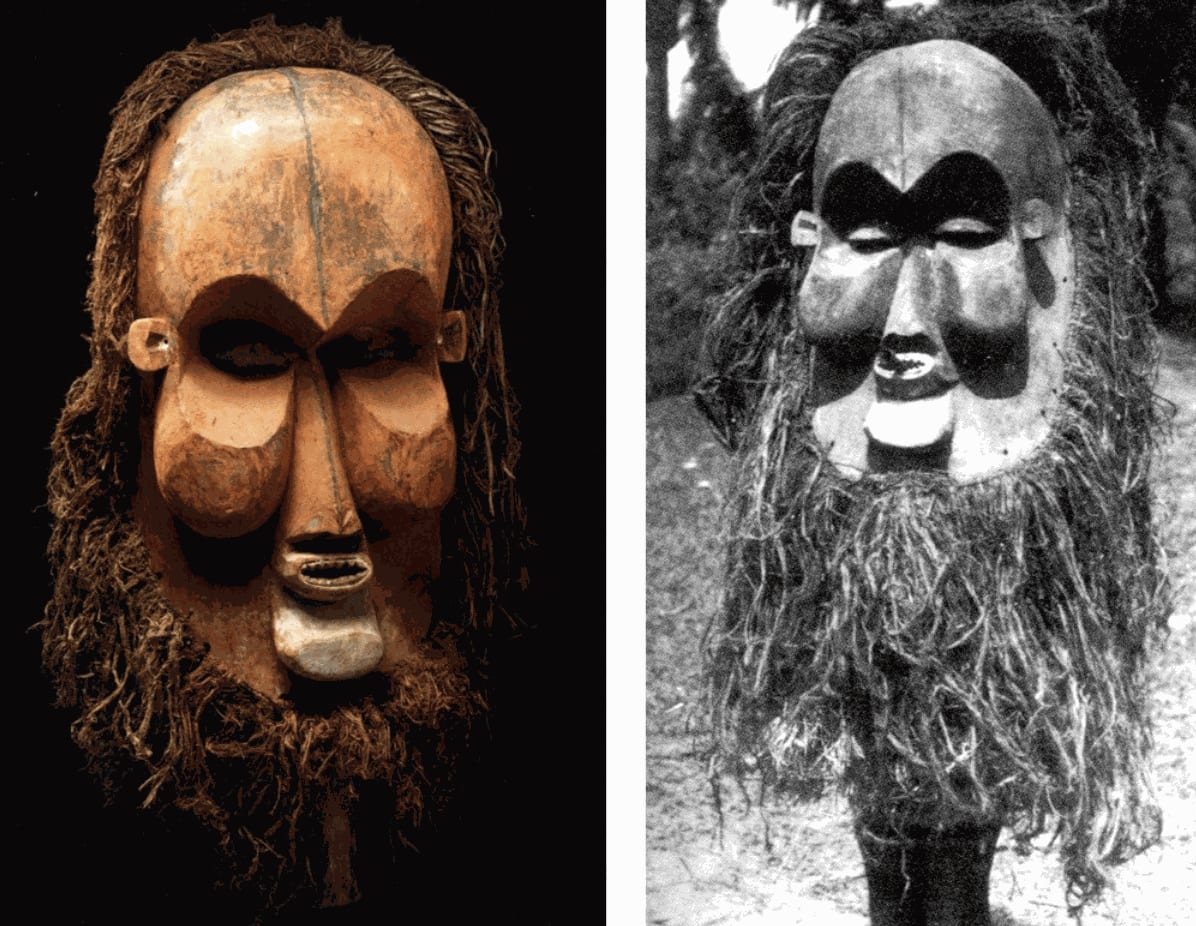

For the first time ever on public view, we are very proud to present this rediscovered kakungu mask at the PAN art fair in Amsterdam this week. Never exhibited nor published before, this mask is one of the handful of its type to remain in private hands. This extraordinary mask was used by Yaka and Suku peoples of south-western Congo in the early 20th century. Both cultures share an institution called mukanda, which is concerned with the circumcision and initiation of young men. Kakungu, the 'red giant', played an important role during this male initiation. The Yaka and Suku consider kakungu as their oldest and most powerful mask. Apart from its extraordinary size, it is characterized by inflated cheeks, massive features, and a prominent projecting round chin. The basic painted colors are red and white, with the chin area generally painted white. Made of a soft wood called mungela (alstonia congensis or ricinodendron), the mask generally was worn surrounded by a full-length fringe of palm leaf stripes called futi or kindua. Kakungu masks were exclusively owned and worn by the charm specialist of the initiation camp called isidika (or kisidikaamong the Suku), as one of the many tools employed by him to ensure the well-being of the boys during this transitory period in their life. Kakungu performers also wore a specific outfit, the ndaka zi kakungu, made from pieces of antelope skin along with various objects such as bells and cut pieces of gourd; and consecrated the mask through the sacrifice of a goat. A kakungu mask was considered well made when it could instill fear in people at first glance, whether it was seen from afar or close.

Private Collection, Brussels, Belgium. Height: 80 cm

This mask was photographed in situ by Hugo Huber (Cf. Hugo Huber, "Magical Statuettes and their Accessories among the Eastern Bayaka and their Neighbours (Belgian Congo)", in: Anthropos 51, 1956, pp. 265-290)

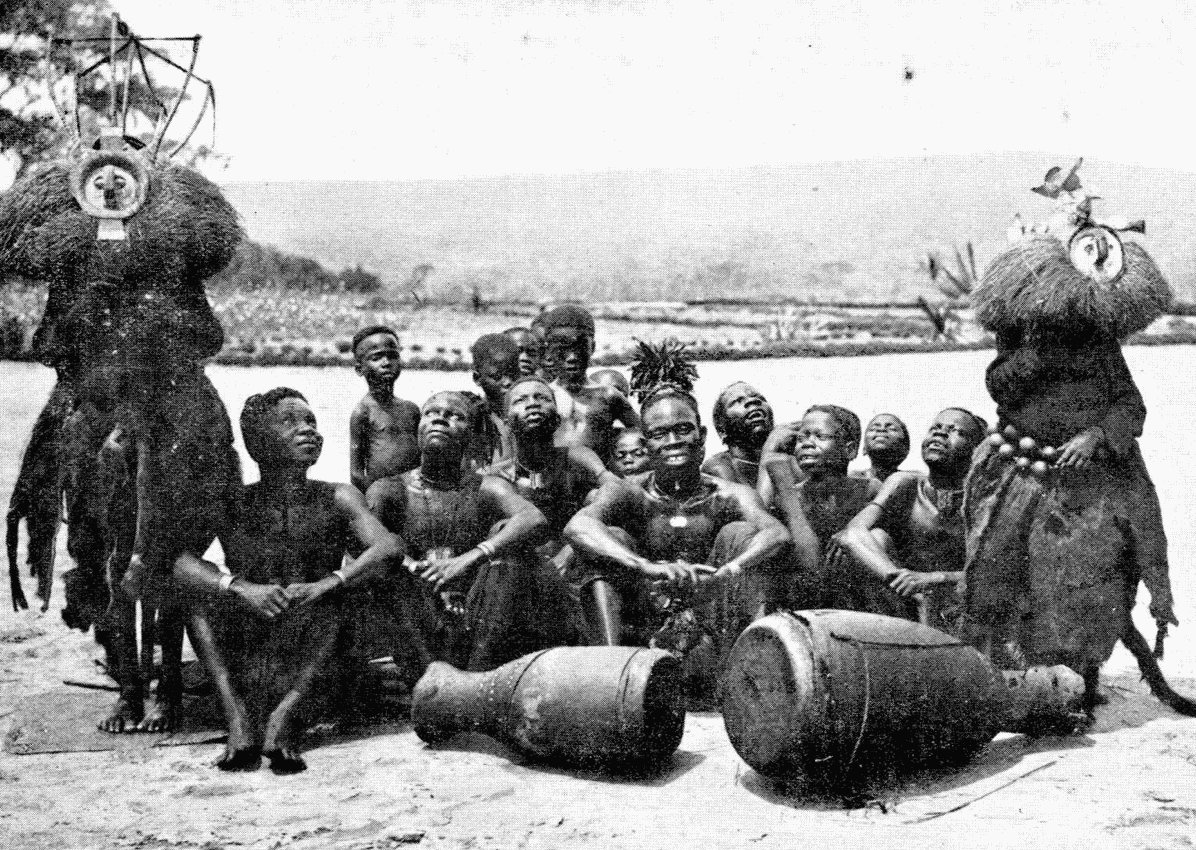

Mukanda was an exclusively male initiation ritual intended to make men out of the village’s boys. At the start of the session, the younglings were taken to an enclosure in the bush where they were circumcised. Afterwards, during several months of isolation, they received training that prepared them for their future lives as adults. They were not only exposed to hazing and deprivation, but also learned to hunt and received sex education in preparation for their marriage. Moreover, they learned to dance with masks. Indeed, at the end of this initiation period and on the return to the village, public masked dances took place. However, unlike the other mukanda masks, the kakungu was not worn by the young, circumcised men and couldn’t truly be considered as a dance mask. Worn by the isidika, within mukanda initiation, the kakungu mask customarily appeared on the day of circumcision, the day of departure from the camp, and occasionally for the subsequent breaking of food restrictions. Its appearance served to frighten the young candidates into obedience and respect for their elders, and to threaten any person secretly harboring evil intentions against one of the initiates.

Yaka initiates in the company of two masked initiates (published in: Plancquaert (Michel), "Les Sociétés Secrètes chez les Bayaka", Louvain: Imprimerie J. Kuyl-Otto, 1930: #17).

Until the 1950s, kakungu visited Yaka and Suku villages the day preceding the circumcision, whereupon everyone hid indoors. The emergence of kakungu in the village was considered particularly harmful to pregnant women. Moreover, the mask wearer possessed the ability to detect a pregnancy even before the community or family was aware of it. He would seize the woman, holding her by the foot, and order the child to go out. To avert harm and please kakungu, shell money was paid by relatives. The satisfied red-faced giant gave the women kaolin clay with which she rubbed her pregnant belly. If no reward was given, it was said that the child might be born malformed or would resemble kakungu!

Collection Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT., USA (2006.51.226). Height: 114,5 cm

On the day of the circumcision, shortly before the actual operation, kakungu appeared again. The German anthropologist Hans Himmelheber recorded that the presence of the mask on this occasion was mainly intended to encourage the young men to be strong like the kakungu with the powerful cheeks. Arthur Bourgeois wrote that among the Northern Suku, the kakungu mask was called out by its assistant (kilendi), who shouted a proverb intended to jolt kakungu into action and sang verses to encourage it. Kakungu would approach the gathering and frighten those present with the characteristic sound "iiiiiiiiiiiiih! iiiiiiiiiiiiiih!iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiih! hum, hum, waka, waka, waka." The kakungu wearer would first seek out the leader of the initiates (kapita), seize his arm, and not release him until the boy's father presented a gift to kakungu. If there was hesitation, the boy would suffer the consequences, namely, the kakungu sickness - illness or misfortune stemming from a curse-placed upon those disrespectful toward the ways of the elders-ancestors. However, the role of kakungu cannot simply be reduced to that of a 'hostage taker': his power was mainly used positively during the mukanda to protect the tundansi (young initiates) against all kinds of threats and aggressions, including those emanating from the baloki (witches) that could enter the camp and cause harm to the initiates. In case a boy bled profusely after removing the foreskin, the kakungu could intervene to stem the flow of blood. Moreover, it was not necessary to wear the mask to fulfill a protective role: as a nkisi (power object) it could act from the shelter where it was housed within or near the initiation site.

Young masked initiates during the mukanda (image published in: Bourgeois (Arthur P.), "Art of the Yaka and Suku", Meudon: Alain & Françoise Chaffin, 1984, fig.113).

The power of this nkisi however was not easy to control, as shown by a story recorded by Hans Himmelheber: one day a certain Yaka chief forbade a mukanda ritual that would take place too far into the bush as predators in the area could endanger the safety of the tundansi. The initiation camp was therefore relocated closer to the village. However, this move meant that the kakungucould not be called upon as its constant presence in the vicinity of the village entailed a high risk of infertility for the women. The ambivalent nature of kakungu, being both threatening and protective, is expressed in the mask’s two color combination of red and white: red is seen as a symbol of blood, vengeance and evil, white, on the other hand, as a beneficial color, particularly linked to health. The white chin was invariably described as a beard. An explanation for this was found in the popular notion that old people with white hair or beard often had anti-social powers and occasionally preyed upon their kinsmen as witches – a notion derived from their having outlived their competitors, and the belief that nothing happens by accident. Kakungu masks, however, are not considered to be personifications of ancestors, nor do they embody spirits.

Collection Royal Museum for Central Africa, Tervuren, Belgium (JS.112). Before 1927. Height: 100 cm.

Collection Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, CT., USA (2006.51.289). Height: 85,7 cm.

Kakungu also intervened at the end of the mukanda. During the closing ceremonies, when the tundansi gathered wood to light a large fire in the center of the village, the isidika wore the mask. Once night fell, he hurried to the village, took a burning log from this big fire and returned to the initiation camp, which he set on fire to signal that the mukanda had ended. However, the kakunguwas not destroyed, as this powerful mask was also used in other contexts besides male initiation. Hans Himmelheber was the first to point out that the red-faced giant also intervened in healing rituals. A common manifestation of the sickness associated with and attributed to kakungu among the Northern Yaka and Suku was sterility. That is, if a man or woman was thought to be sterile, members of the person's lineage approached a diviner, a nganga ngombo, and if the principal cause of the condition was attributed to kakungu, a kakungu owner was sought to give the appropriate remedies. As noted by Himmelheber, the treatment involved confrontation with the mask in a small hut for a period of several days. However, this system of healing was used very little as the kakungu were rare and were regarded as exalted therapeutic agencies that should not be systematically called upon. Among the Southern Yaka, kakungu would come out at a new moon in order to cure. With token gifts of eggs or money, the sick approached the cabin where the mask was kept. The kakungu wearer emerged, accepted the gifts with one hand while hiding the eyes of the mask from the donor with the other, and then turned the mask away. The patient would then be treated with another charm held by the mask wearer.

A kakungu mask and a kaseba mask photographed by Hans Himmelheber in 1938 (published in: Himmelheber (Hans), "Negerkunst und Negerkünstler", Braunschweig, Klinkhardt & Biermann, 1960:326, #254).

Although it is the heaviest wooden mask carved by the Yaka and Suku, kakungu also had a reputation for tremendous jumping feats. Accounts Arthur Bourgeois collected tell of kakungu's ability to jump from the village into the middle of the forest, and to jump over cabins or even the tallest palm trees. Its ability to travel great distances in only seconds was also recalled. Another of its reputed aspects was that of controlling the weather. The mask was used to bring rain as well as to drive away an approaching storm. Julien Volper suggests that this function might also have had a role within the mukanda. After all, warm and dry weather was preferable after circumcision, in view of good wound healing. A sudden storm or persistent rain could cause medical complications or serious infection. Kakungu’s ability to control weather as well as to perform jumping feats is cited in sung verses associated with this mask, while Himmelheber reports the use of a kakungu to threaten a tornado as it approached.

Exhibition view “Giant Masks from the Congo”, Bellvue museum Brussels, 2015

Based on 29 documented kakungu masks in museum collections, Arthur Bourgeois identified several regional styles. Style A masks such as ours are general supported by a vertical handle at the base. The projecting chin occasionally assumes a spherical shape, repeating the bulging of the cheeks, and an oval mouth protrudes in a pout-like manner. A massive forehead rises from a flat background base or ridge. In coloring, the surface is reddened, and the chin painted white. The only decoration apart from the white chin is a vertical black (or blue) line streaked down the forehead and along the brow. Of the eleven masks of this variety collected between 1922 and 1953, eight derive from the locale of Jesuit mission stations at Kingungi and Yeye on the Lukula River, and one example is from Kimbau on the Inzia River. The use of kakungu masks ended with the widespread destruction of traditional charms in the mid-1950s and their replacement with what was considered to be a more powerful foreign variety. Since nineteenth-century European intervention, several such movements had occurred among the Yaka and Suku. Beginning in 1954, a Holy Water Cult spread throughout the Kwango region supervised in part by Catholic missionaries. Several Yaka groups briefly took it up and later returned to traditional charms, although for reasons that are not quite clear, kakungu in its mask form was never again reinstated. This previously unrecorded kakungu presents an important addition to the limited number of masks of this type to remain in private hands. With its beautiful coloration, extensive sings of use, symmetrical rendering of the carved features and visual balance between chin and forehead this gigantic mask stands out as a visual masterpiece of African art.

Further reading:

Bourgeois, Arthur, “Kakungu among the Yaka and Suku”, African Arts, Vol. 14, No. 1, November 1980, pp. 42-46+88

Himmelheber, Hans, "Les masques Bayaka et leurs sculpteurs," Brousse 1, 1939, pp. 19-39

Volper, Julien, "Giant Masks from the Congo. A Belgian Jesuit Ethnographic Heritage", Tervuren, Royal Museum for Central Africa, 2015