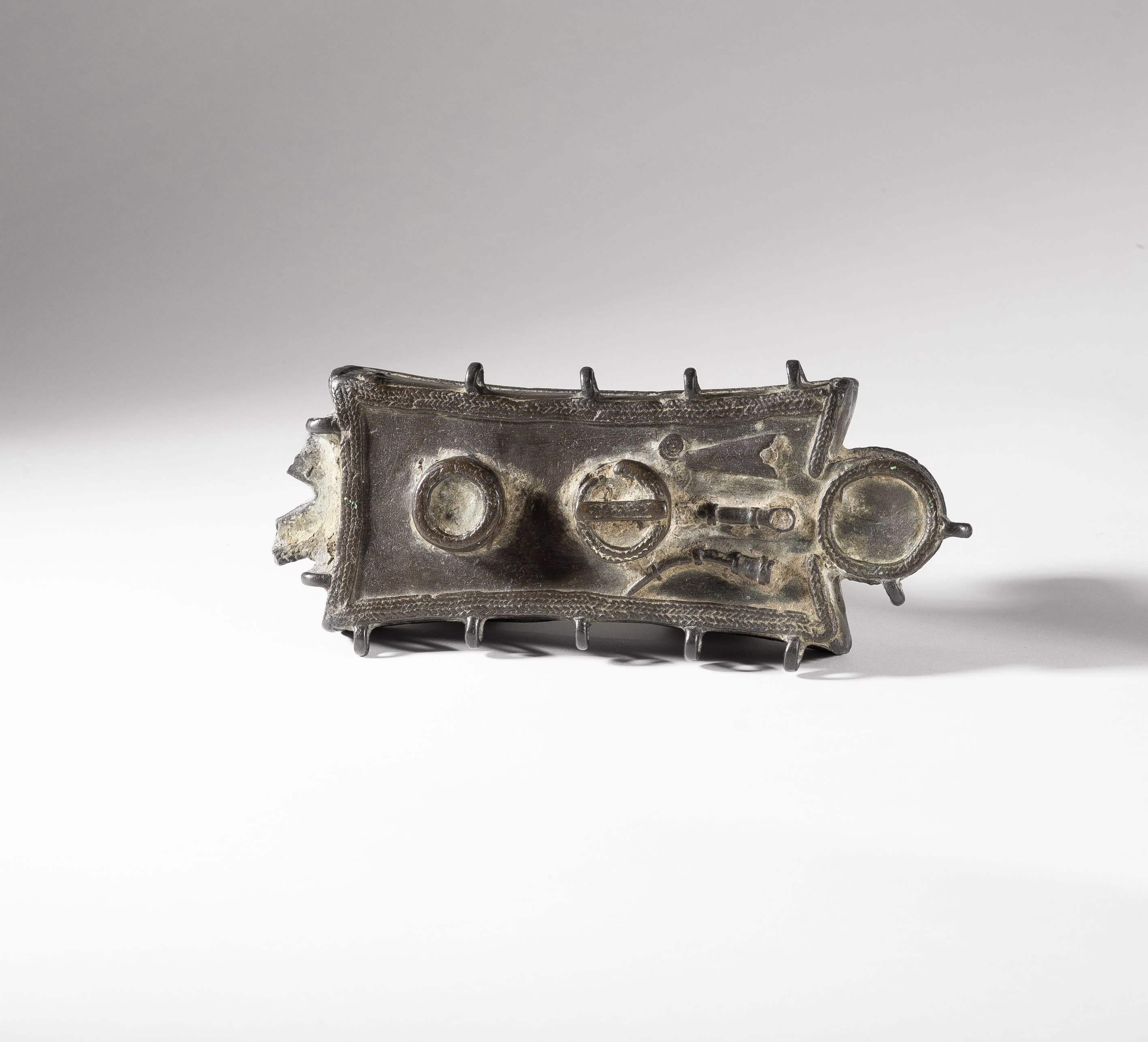

RITUAL OBJECT, "OFO"

Anonymous Isoko or Urhobo artist

Nigeria, 15th-19th century

Bronze. 7 x 21 cm

Provenance:

Private Collection, Germany

Petr Zubek, Düsseldorf, Germany, 2023

Duende Art Projects, Antwerp, Belgium

These ritual objects are known among various communities in southeastern Nigeria and exist in various forms and materials. Ofo are little known, perhaps because only a small percentage of the thousands once in existence were elaborated into what are now labeled works of art. Yet, as we will see, the ofo is one of the central ritual objects among the Igbo, primarily representing ancestral power and authority and the key values of truth and justice. In his 2021 magnus opus “The Lower Niger Bronzes”, Philip M. Peek dedicated a chapter to these enigmatic objects, assembling all information on the subject in an excellent study (pp. 54-70). Standing on the shoulder of a giant we’ll quote extensively from his publication in this essay.

A collection of different sizes of metal-encased ofo type in the royal palace at Ossomala. Published in: Ejizu, Christopher, “The Taxonomy, Provenance, and Functions of ofo: A Dominant Igbo Ritual and Political Symbol”, Anthropos, Bd. 82, 1987, p. 460, plate 2.

An ofo’s particular form is derived from the appearance of a specific tree branch used for political and religious ritual purposes among southern Nigerian cultures. All people living in the Niger Delta and Riverain areas, i.e. the Isoko, Urhobo, Igbo, and Ijo, recognize and venerate the ofo (Detarium senegalense) tree and its unique branches, but they have all found different ways by which to represent this sacred tree for political and religious purposes. Virtual identical cast-metal forms are found among the Isoko and Urhobo (ovo), Igbo (ofo), and Ijo (ovuo) - clearly the names are cognates, and they identify similar beliefs and practices. Symbolizing the ancestors, ofo derive originally from the tree of the same name that grows throughout southern Nigeria. While all these cultures keep bundles of the sacred tree’s twigs in their ancestral shrines, there are also additional representations of ofo in copper-alloy forms, which seem to differ by region. The ofo of southern Nigeria are an excellent example of the “permanentization” of a symbol’s power and value by reproducing it in a copper-alloy form. (Peek, op. cit., p. 54).

Surprisingly, while ovo twig bundles are used by the Urhobo, the Urhobo expert Perkins Foss confirmed to Philip Peek they did not know copper-alloy ovo (Peek, op. cit., p. 56). The presence of ‘legs’ might be indicative of an ofo’s origin. Philip Peek never observed an ofo with legs among the Isoko, concluding this must be an Igbo tradition. Clayton was told the ‘legs’ were to keep the object from touching the ground, a contact that would contaminate it. (Peek, op. cit., p. 57) Peek has recorded nine ofo with a rectangular table-like form as ours, averaging 22,9 cm in length and resting on four supports (clearly not legs as with other ofo). The origin of this form is unknown. It has a circular concave feature in an hour-glass form as a receptacle for chalk at one end. There generally is a flat flange or a ring at the other end. All examples of this type have small eyelet rings around the edge from which small crotal bells were once attached. Another consistent feature are the decorations on top. Each has, in slight relief, two small circles and three oblong objects (possibly representing a gong, ofo, and horn). Twisted rope lines decorate the edges. (Peek, op. cit., p. 60).

Isoko Abrebo shrine, with bronze and wooden ovo inn a cow’s jaw bone. Photographed in Okpe by Philip M.Peek, 1971. Published in: Peek (Philip M.) , “The Lower Niger Bronzes: Beyond Igbo-Ukwu, Ife, and Benin”, New York: Routledge, 2020: plate 3.

Besides the present previously unpublished table-like ofo, six other examples of the type have been identified for this study. Only the example collected by the well-known art dealer Philippe Guimiot still features its original bells. Two others were photographed in the royal palace at Ossomala (Ossomari, a Riverain Igbo group) by Christopher Ejizu in the 1980s. The Fowler Museum at UCLA has one its collection (X91.416). Another was once sold by the Belgian art dealer Lucien Van de Velde in the 1970s. The Brussels-based dealer Pierre Loos exhibited his collection of ofo during the 2009 edition of the Brussels Non European Art Fair (BRUNEAF), publishing a heavily encrusted example in the catalog and featuring a second ofo of the table-like type in the show. Philip Peek mentions one unpublished example in the collection of Mark Clayton. The uniformity in style and the consistent arrangement of similar decorative relief motifs on top suggests these were all made in the same regional casting center. Clayton’s ofo was examined by XRF analysis at UCLA. According to the result, copper was by far the dominant component, the test showing over 80 % copper with only surface trace elements of tin, zinc, and lead (op. cit., p. 66). This suggests significant age as later copper-alloy works generally have increasing amounts of lead due to the growing European trade. Considering the dates obtained by testing for a number of copper-alloy ofo, Peek concluded the tradition has existed for a minimum of 500 years (Peek, op. cit., p. 69). These highly revered objects were treated as important heirlooms and passed down from generation to generation.

Collection Fowler Museum at UCLA, USA - promised gift of Mark Clayton.

The tree at the heart of the ofo complex is found throughout western Africa. Originally recorded in Senegal – as its botanical name, Detarium senegalense, indicates – it is utilized in various ways from its popular fruit and wood to its medicinal and cosmetic properties. How it came to be sacred tree among the Igbo and Isoko is unknown, although its red sap and unique manner of dropping its branches may have caused such attention. The tree’s remarkable twigs are 10 to 15 cm in length and shaped like the knotty joints of a human bone; with a slight depression at one end, the twig is reminiscent of a human forearm and cupped hand. Some refer to the concave end as ‘spoon-like’. These twigs can be collected only when fallen to the ground. They may be employed individually but are usually gathered in bunches of seven or nine, bound (often with wire), and placed on altars. Such configurations, usually covered with kaolin chalk and other offerings, are the most common ofo among all Isoko and Igbo peoples. These small branches as well as the bronze replicas average about 16,5 cm in length. Henderson summarized these traditions among the Onitsha Igbo: “Perhaps the most important medicinal medium is the tree called ofo. Its twigs are somewhat phallic in shape and fall naturally away from the branches of their paternal tree just as, it is said, human sons grow as dependent of their fathers but in time become separate from them. These twigs, picked from the ground by males and appropriated as their personal property, are called ofo Okpala and represent the supposedly intrinsic qualities of individual maleness and paternity. (Henderson, R.N., “The King in Every Man: Evolutionary Trends in Onisha Ibo Society and Culture”, New Haven, 1972, pp. 118-119). (Peek, op. cit., pp. 54-57)

Group of Lower Niger Bronzes (including a rectangular ofo type with crotal bells). Photo: archives Philippe Guimiot. (published in: Peek, Philip M., “The Lower Niger Bronzes”, New York, 2021, p. 61, fig. 6.4).

No matter the form that the various types of ofo take, they are employed in much the same way. There is much literature about its importance in Igbo communities and these practices are echoed among the Isoko and Edo. The centrality to religious and political authority and ritual is demonstrated by the variety of their uses and meanings. The detarium senegalense twig, alone and in bundles and in its copper-alloy versions, is the most important representation of the ancestors in southern Nigeria. Among the Igbo and neighboring cultures, ofo is used for daily prayers, ancestral veneration, and oath-taking. It represents an individual’s ritual authority and personal integrity. According to Bentor the ofo is a symbol of seniority and authority, justice and propriety, and ritual validation in numerous social interactions. For example, it is carried by adult Igbo men to be used whenever offering prayers or oaths and is sworn upon in order to prove one’s innocence. (Peek, op. cit., p. 63). The concept of innocence, agu, is fundamental to the Igbo ethos, demonstrated by the frequent use of the saying “May this ofo kill me if I am wrong.” In Igbo traditional religion, one can only manipulate spiritual powers if one can face them with “clean hands”. The ofo is a personal object. Its owner often takes it in a leather bag to meetings and ceremonies where it will receive libations. The ofo may be carried to provide protection during a journey and to help in fighting, and it can also be used to cast a spell, for example, to curse a thief. Upon the owner’s death the ofo is discarded, or if the person was an important man, his senior son may place it in the ancestral shrine. A man usually obtains an ofo when he reaches his middle years, even if his father is still alive, because “he must have something to hold when he prays, he cannot expect the elders to do it all.” Ownership of an ofo indicates an independent individual who can communicate with ancestors and deities without resorting to a mediator. The primary meaning of the ofo is to be found in its role within the family. The okpala (senior son) plays a central part all aspects of the group’s life. As the chief priest and ceremonial family head, he is an intermediary between the living members of the family and the ancestors. Ofo is the most important symbol of the okpala’s authority, which often derives from the ofo’s being given to him by the ancestors through his father. At council meetings and other gatherings, the hierarchy of men and families is represented by the order in which the ofo are arranged for receiving libations. (Bentor, Eli, “Life as an Artistic Process: Igbo Ikenga and Ofo”, African Arts, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1988: pp. 67-68) As Herbert M. Cole wrote in 1982 (“Mbari, Art and and Life Among the Owerri Igbo”, Bloomington, 1982, p. 10) “the Ofo itself dramatizes the spiritual basis of even the most secular matters even today, for its power represents the authority of the high god, Chineke, channeled through lineage ancestors, Ndichie, without whose support and concurrence man dare not act.”

Collection Ambre Congo/Pierre Loos, Brussels, Belgium, 2009. Published in: Expo cat.: “BRUNEAF, Brussels Non European Art Fair XIX”, Brussels, 2009:13 (Ambre).

An ofo is a dynamic symbol of one’s independent relationship with the ancestors and of one’s authority within the family unit and social group, such as the dibia (healers and diviners) association. In practice ofo is an action, not just an object symbolizing the ancestors, political or religious authority. The significant element is the words of the oath that is sworn while holding one’s ofo. Thus, the object is a sign of the action; the primary action of swearing if symbolized by the object, which is secondary. It should be noted this sacred instrument had to be ritually activated in order to function effectively, otherwise it would remain an inert object. In addition to the inherent properties, physical and metaphysical, of the copper-alloy (hardness, durability), these sacred emblems of personal authority and integrity were regularly revitalized by sacrificial offerings and prayers – as observed in the present example’s wear and patina. (Peek, op. cit., p. 63).