SHRINE STATUE "OKPOSI"

Anonymous Igbo artist

Nigeria, Early 20th century

Wood. 66,6 cm

Provenance:

Abdoulaye Ousmane, Brussels, Belgium, 2015

Private Collection, Antwerp, Belgium, 2015-2023

Duende Art Projects, Antwerp, Belgium, 2023

According to the scholar Herbert Cole, this abstract cylindrical sculpture likely is an okposi, which was typically kept together with ikenga and other title-equipment in an obi or titled man’s compound (personal communication, 15 October 2015). Frank Starkweather refers to okposi or okpensi as being single shrine figures to the ancestors, found in the gate houses to the traditional compounds where men gathered and received their visitors (Starkweather (Frank), “Traditional Igbo Art: 1966”, University of Michigan, 1968, p. 70). Eli Bentor wrote that such a carving was kept in the irummo, the personal shrine within the obi. The owner made offerings to it whenever he wished to ensure success in any kind of venture (Bentor, Eli, “Life as an Artistic Process: Igbo Ikenga and Ofo”, African Arts, Vol. 21, No. 2, 1988: p. 70).

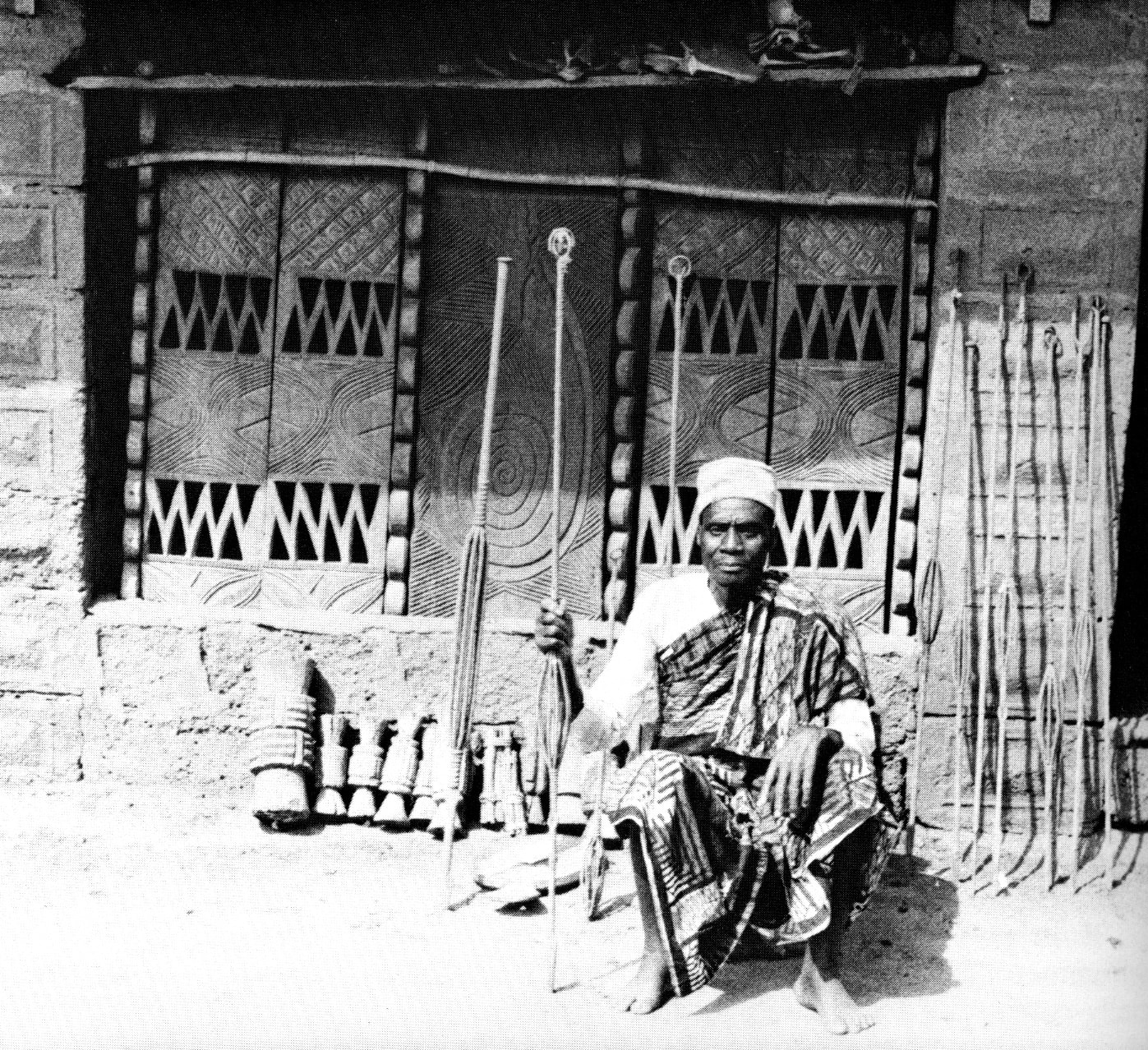

Transitional cement obi with traditional ‘eyes of spirits’ panel plus the okposi and staffs which are normally enshrined on the altar behind the panel. Photographed in Ezeagulu Aguleri by Herbert M. Cole in 1983. Published in: Cole (Herbert M.) and Aniakor (Chike C.), “Igbo Arts, Community and Cosmos”, Museum of Cultural History, Los Angeles: University of California, 1984:66, #111.

The ancestors occupied an intermediary position between the living and the spirit world in traditional Igbo belief. Prayers, offerings, and sacrifices were presented to the ancestors at regular intervals to keep the relationship fruitful to those presently occupying the family land. The Igbo called their ancestors ndichie or ndimmo. Both terms were used for the deceased members of patrilineal kin groups (clans or lineages) who were believed to retain a close interest in the affairs of their descendants and to intervene on occasion for either good or ill according to the kind of relationship that has been maintained between the living and the dead. A person who lead a good life and did not neglect to make regular offerings to his ancestors would be blessed by them so that his affairs and his family life prospered. A person who incurred the wrath of his ancestors through quarrelling within the family or through neglect of the proper offerings could be struck with sickness or other misfortune. The Igbo used carvings, called okposi, to represent the ancestors on domestic shrines. A man’s relation with both his ancestors and his personal guardian spirit (ikenga) expressed the notion that his destiny was not entirely of his own making but was determined partly by forces beyond his control (Boston (John), “Ikenga”, Federal Department of Antiquities, Nigeria, 1977, p. 16).

Okposi, bound umuada, ‘daughters’, sticks, a chalk serving plate, and details of wrought-iron staffs. Photographed by Herbert M. Cole in Ezeagulu Aguleri in 1983. Published in Cole (Herbert M.) and Aniakor (Chike C.), “Igbo Arts, Community and Cosmos”, Museum of Cultural History, Los Angeles: University of California, 1984, p. 11, #25.

The central section of this sculpture is deeply carved with several motifs such as a standing figure, two diminutive ikenga with horns, a serpent, and grooved abstract cylindrical forms probably representing ofo. Kept together with ikenga it is worth exploring this other type of Igbo ritual sculpture here. I-ke means strength or power, n-ga means place of strength. Ikenga thus literally means place of strength. In the case of the Igbo man that is the bicep of the right arm. If a man has a strong right arm, he can achieve success and become self-reliant. The ikenga then, is a statue dedicated to a man’s ability to make his way in the world. The spirit of the ikenga could be considered the manifestation of the Igbo their high need to achieve. An Igbo man would have made a sacrifice to his ikenga for success in trade, war, hunting, and farming. The sacrifice could be kola nuts, but more commonly a chicken, whose blood and feathers were ceremonially applied to the statue. Unlike most Igbo carvings which were commissioned personally, ikenga were readily available in the market. A typical time for a male to acquire an ikenga was as a village youth moving into his own house in his father’s compound, or when having difficulties making his fortune. The statue gained strength when it was taken home by the purchaser and consecrated with palm wine and kola nuts. Ikenga were most prominent in Northern Igboland but unknown among the Eastern Igbo. (Starkweather, op. cit., pp. 78-79).

Most of these figures left Igboland in large numbers during and just after the Nigeria- Biafra civil war (1967-1970). During the war years literally thousands of Igbo art objects were burned, destroyed or lost; many others left Nigeria, partly because of the permeability of the border between Nigeria and Cameroon, when everyone was focusing on the war. By the time the war began, an influx of Christianity and Islam had deprived shrine figures of their original meaning, but they started a new life as collectible artworks in public and private collections in Europe and America. Earlier in the 1950s and 1960s community cult shrines had already begun to detoriate from neglect, although their figural sculptures mostly remained intact. Two other sculptures from this master carver could be identified, one published by Alain Dufour in 2004, the other in the Marshall & Caroline Mount Collection (New Jersey). Their iconography is almost identical, notwithstanding the presence of a sculpted head on the upper section. Herbert Cole considers these stylistically closer to Igala ikenga forms than the more typical Igbo ones. He has suggested an Igala origin – more specifically from the Ibaji region adjacent to the northern Igbo – could also be possible (personal communication, 15 October 2015).