Duende's stories attract our readers' attention since 2013 (previously hosted on brunoclaessens.com) and wishes to provide a useful resource for information on art of the African continent and its diaspora. Stories include exhibition announcements and reviews, interviews with artists, discoveries, new research, auction news, etc.

We welcome contributions and feedback. So, if you wish to share an opinion about a story, provide additional insights or if you have a news story, then please get in touch.

-

Our mask on view this week at the PAN art Fair in Amsterdam

Our mask on view this week at the PAN art Fair in Amsterdam -

Female bust, Anonymous Pende artist. Early 20th century, D.R. Congo. Wood, 63 cm. Provenance: Private collection, Belgium

Female bust, Anonymous Pende artist. Early 20th century, D.R. Congo. Wood, 63 cm. Provenance: Private collection, Belgium -

-

-

Installation view UNSETTLED.

Installation view UNSETTLED. -

-

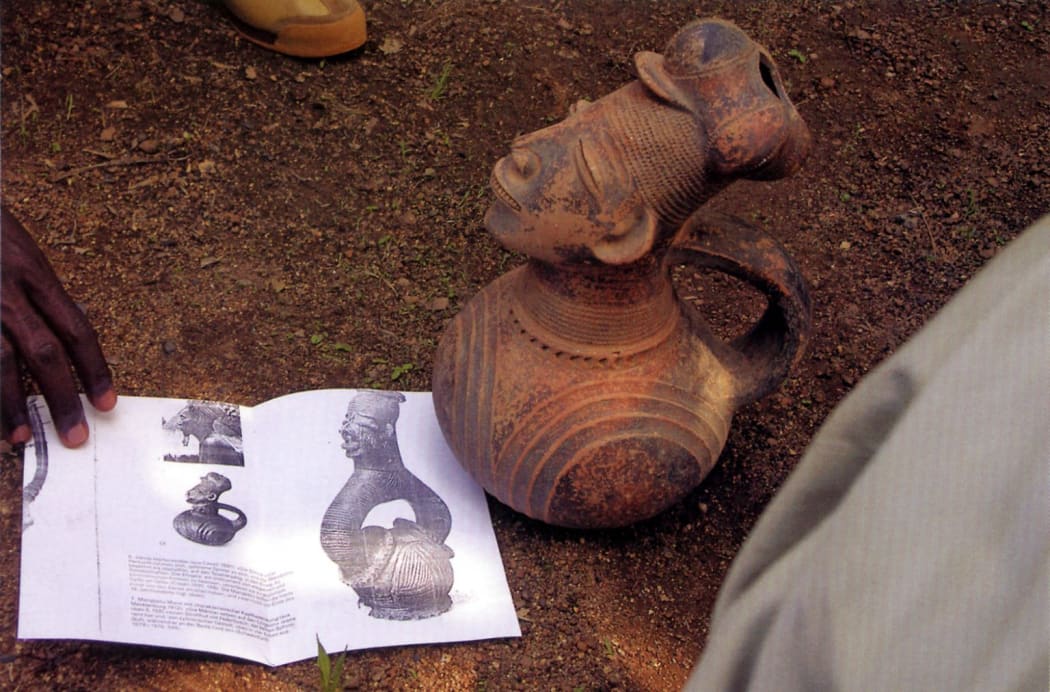

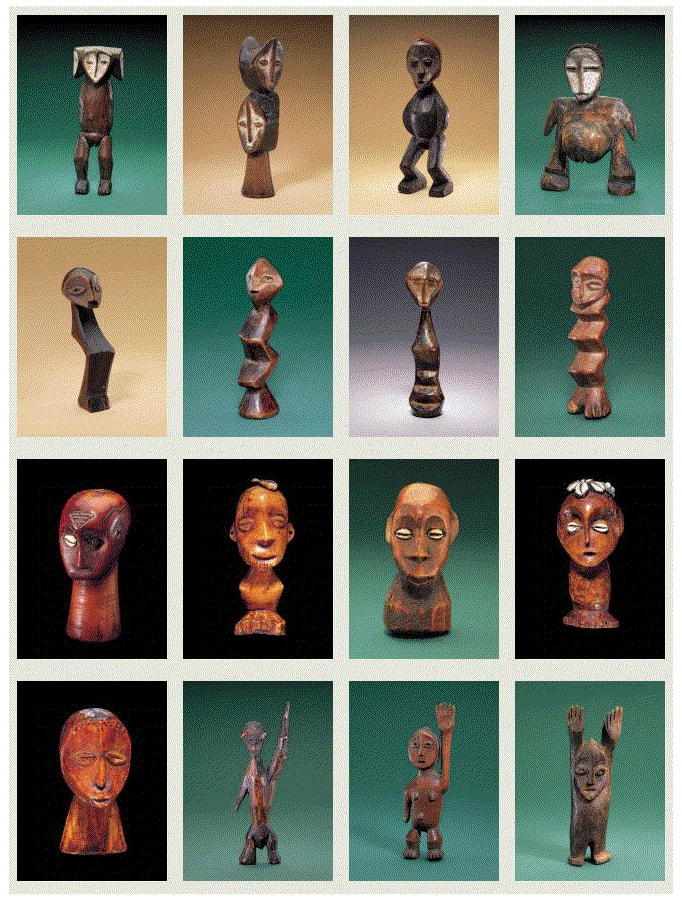

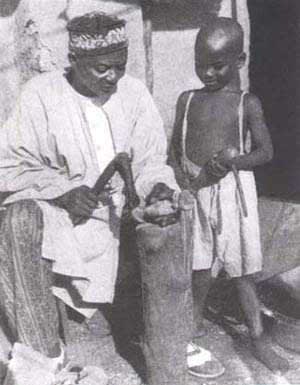

Image courtesy of Lorenz Homburger, 2 March 2006. Published in: Homberger (Lorenz) and Christine Stelzig, “Contrary to the Temptation!. An Appeal for New Dialogue Among Museums and Collectors, Scholars, and Dealers” in African Arts, Vol.XXXIX, #2, Summer 2006, p. 6, #2

Image courtesy of Lorenz Homburger, 2 March 2006. Published in: Homberger (Lorenz) and Christine Stelzig, “Contrary to the Temptation!. An Appeal for New Dialogue Among Museums and Collectors, Scholars, and Dealers” in African Arts, Vol.XXXIX, #2, Summer 2006, p. 6, #2 -

-

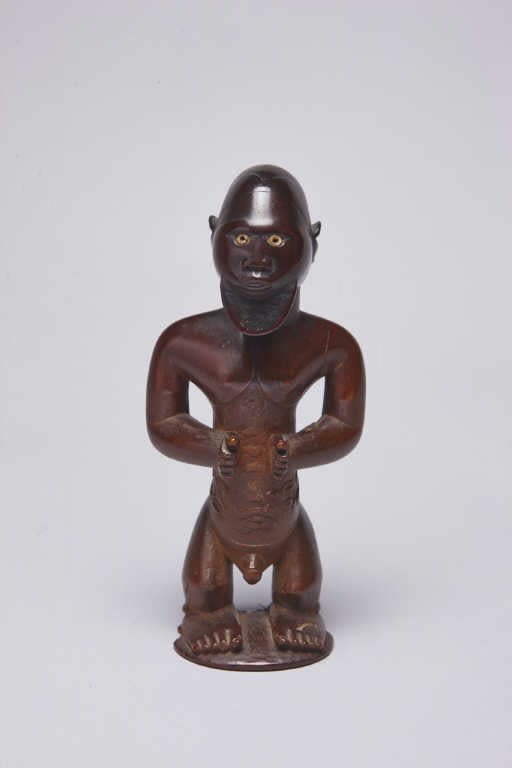

Image courtesy of the Horniman Museum, London (#10.2.62/34). Height: 27 cm.

Image courtesy of the Horniman Museum, London (#10.2.62/34). Height: 27 cm. -

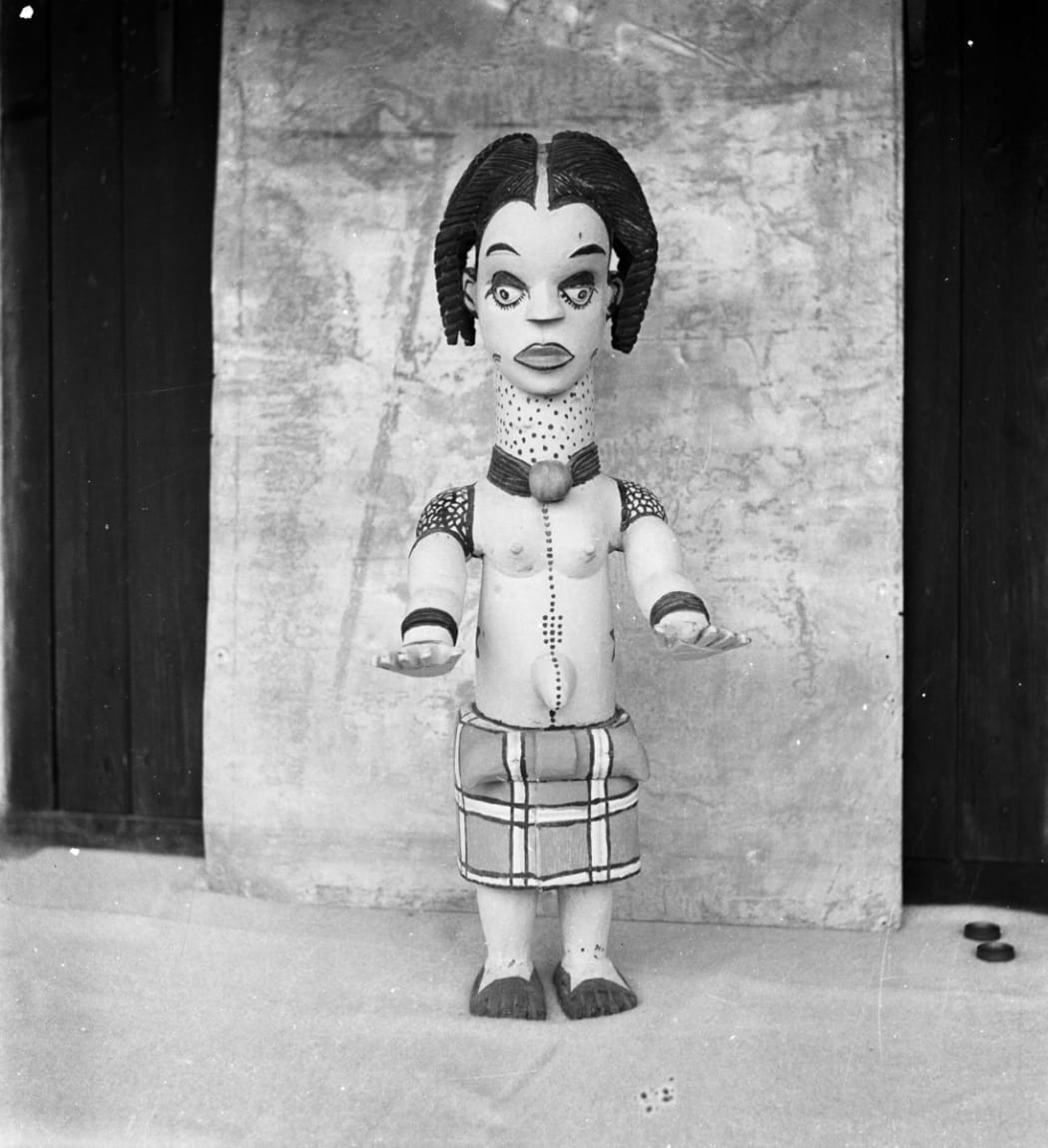

A ‘modern’ Anang female doll figure, carved in wood and painted in a ‘naturalistic’ style. Photographed by G.I. Jones in South Eastern Nigeria between 1932-1938. Image courtesy of the Cambridge Museum of Archeaology and Anthropology (N.13196.GIJ).

A ‘modern’ Anang female doll figure, carved in wood and painted in a ‘naturalistic’ style. Photographed by G.I. Jones in South Eastern Nigeria between 1932-1938. Image courtesy of the Cambridge Museum of Archeaology and Anthropology (N.13196.GIJ). -

-

-

-

Another interesting story I came across while reading Robert Dick-Read’s book “Sanamu. Adventures in search of African Art”. When he set up his art gallery in Mombasa in the early 1950s, ninety percent of the works he bought for export came from the Wakamba carvers of the Kenya’s Machakos district. Dick-Read relates:

The history of the Kamba curio carving industry is one of the most phenomenal success stories of modern Africa. Before the first world war, apart from several types of stools, ceremonial staffs, and household utensils, the Wakamba showed no propensity for creative arts and crafts whatsoever. However, in 1958, an economist (Walter Elkan) investigating the then blooming Kamba carving trade estimated that in the peak years of 1954 and 1955, the people of one Kamba village alone (Wamunyu) grossed at least £ 150,000 and possible as much as £ 250,000 from the sale of woodcarvings! The beginning of commercial carving among the Wakamba is attributed to a man named Mutisya Munge who, before the first world war, was known throughout Ukamba for his excellence as a craftsman. Before the war his work was confided to traditional objects such as stools; but whilst serving with the armed forces away from home he began to occupy his idle hours by carving ‘pictures’ from his imagination, for his own amusement. He found that his officers and other Europeans were intrigued by his carvings, and after the war he devoted more and more of his time to producing them for sale. For the first year or two, reluctant to let others in on his idea, he used to hide himself away in the bush and carve in secret. Inevitably, however, his secret was discovered and before long a number of other carvers in his village had copied his patterns and begun to sell their work in Nairobi. The market among white men seemed inexhaustible; and between the wars the number of carvers increased. The trade received its first big fillip during the second world war, when large numbers of British soldiers came to Kenya. Then after 1945, with the rapid increase of tourism to Kenya, it expanded yet again. By now firms abroad were beginning to take an interest, and the export trade began to develop. The number of carvers was continuously increasing, and the street corners of Nairobi and other main towns became crowded with vendors, all of whom did brisk business. There seemed no end to the expansion, and in the fifties the industry continued to grow. By 1954-55 there were up to 3,000 part-time or full-time carvers, almost all of whom came from Wamunyu village and the surrounding area.

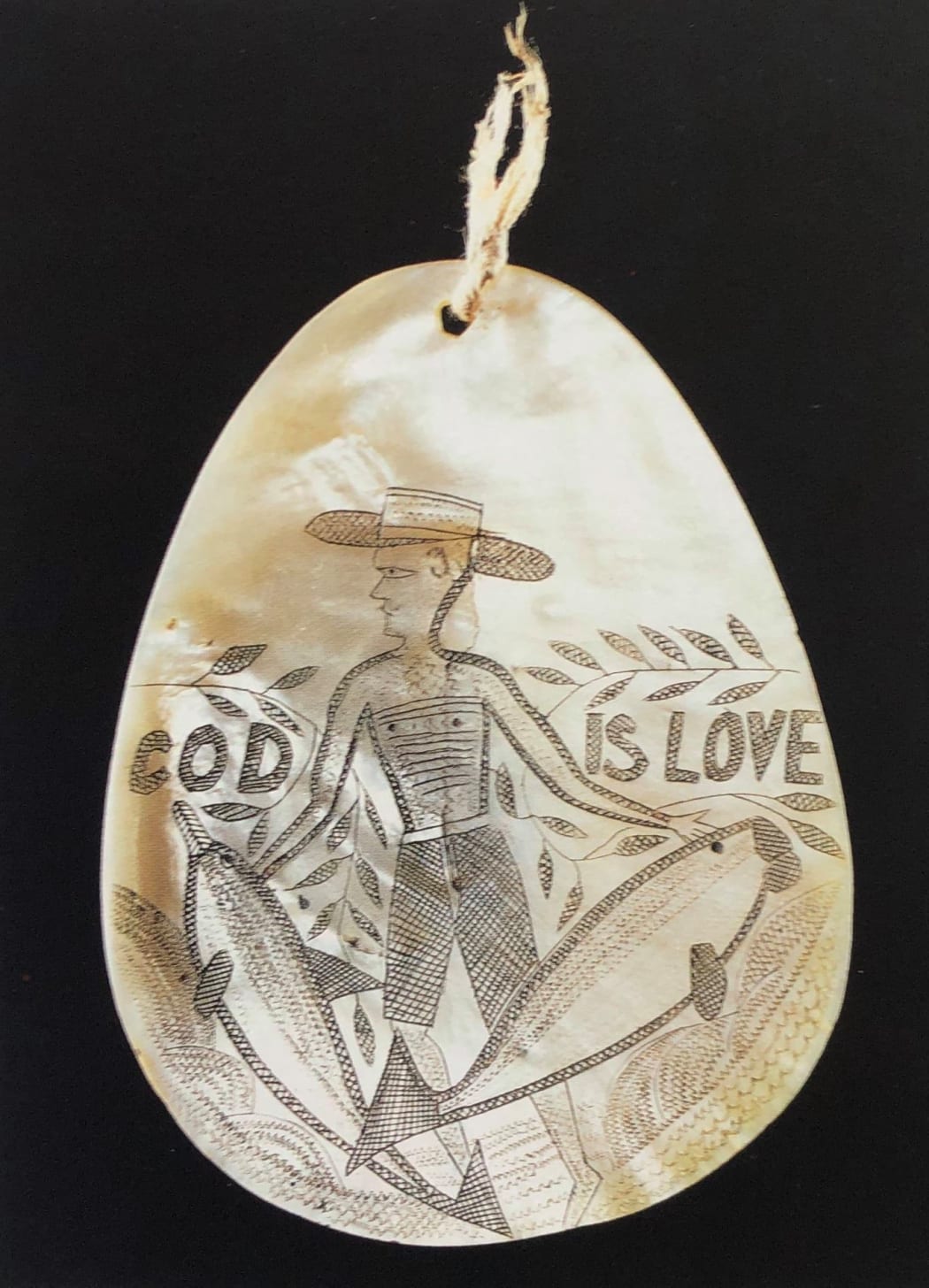

Dick-Read goes on to describe his many visits to Wamunyu to buy basket-loads of sculptures (p. 22 and continued) and how Mutisya’s son, Mwambetu Munge would end up in London, carving African curios in English oak. My additional research on Mutisya Munge revealed he did indeed serve with the British Carrier Corps in Tanganyika.While on a visit to a Lutheran mission near Dar-es-Salaam, he encountered the commercial and innovative potential of carving in a Lutheran mission and learned new forms of practice from Zaramo sculptors in the hardwoods of ebony and mahogany. Once back in Wamunyu, Mutisya would start the family business that would mean the start of the Kamba export art market. Below an example of the type of statue he was famous for.

Such small, delicately carved wooden sculptures were known as askarifigures, becoming typical of colonial production by Kamba craftsmen between the World Wars, and produced before the influences of nationalism and mass tourism. Askari in fact is a Swahili word with an Arabic root that refers to an armed attendant or guard. The key characteristics of these figures are a frontal pose, schematic representation of features, a relatively large head, often with shining eyes and protuberant ears; fine execution and finish; subtle colouring, and strong attention to detail in clothing and other aspects of adornment. Such details are observed in the depiction of askariuniforms, replete with chord lanyard, shoulder epaulets, leggings and even further definition in the accessories (badge, hat shape, arm stripes) to specify status. The sculpted subjects soon would be expanded dramatically into a thriving industry, producing all kinds of wooden sculptures going from depictions of Masaai warriors to all types of animals.

However, the story is not finished. Later in the book Dick-Read relates his contacts with two Americans, Al Kizner and Nat Karwell, who ran a store in the Bronx named ‘African Modern’. In the mail one morning Dick-Read received a gift from Al – a book on African art with a large number of photographs of magnificent pieces of traditional African sculptures. He writes: “Though unquestionably a generous gift, there was no doubt in my mind that there was a secondary motive in Al’s choice of this present for in an accompanying note he remarked that it would be good to receive a few consignments of the type of work shown in the book. What I believe he had in mind was that I should have the photographs copied by Kenya craftsmen..” – and so, my dear friends, we have a first-hand explanation why so many fakes going around are clearly copies of known masterpieces.

-

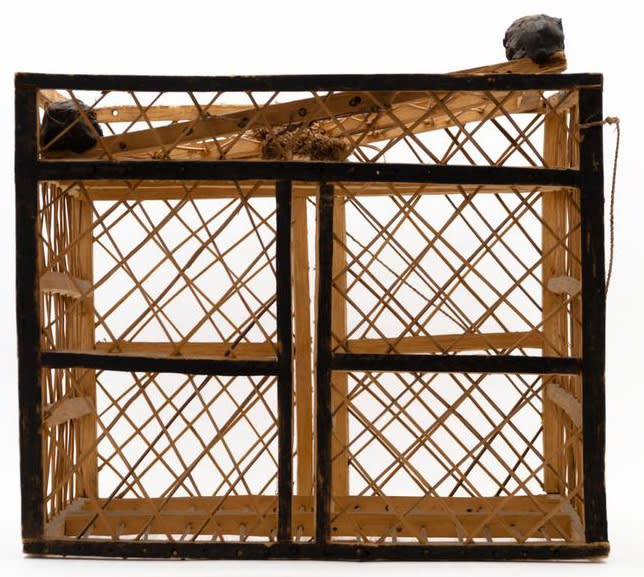

Image courtesy of Gi Mateusen.

Image courtesy of Gi Mateusen. -

-

-

-

-

Right: Mbembe artist; male figure with rifle; 19th to early 20th century; wood; 77.8 cm; gift of Heinrich Schweizer in memory of Merton D. Simpson, 2016-12-1; left: Mbembe artist; female figure; 19th to early 20th century; wood; 68 cm; museum purchase, 85-1-12. Image courtesy of the National Museum of African Art.

Right: Mbembe artist; male figure with rifle; 19th to early 20th century; wood; 77.8 cm; gift of Heinrich Schweizer in memory of Merton D. Simpson, 2016-12-1; left: Mbembe artist; female figure; 19th to early 20th century; wood; 68 cm; museum purchase, 85-1-12. Image courtesy of the National Museum of African Art. -

-

-

Pende mask, D.R. Congo. Height: 30 cm. Image courtesy of Studio Philippe de Formanoir – Paso Doble. Collection Javier Peres, Berlin.

Pende mask, D.R. Congo. Height: 30 cm. Image courtesy of Studio Philippe de Formanoir – Paso Doble. Collection Javier Peres, Berlin. -

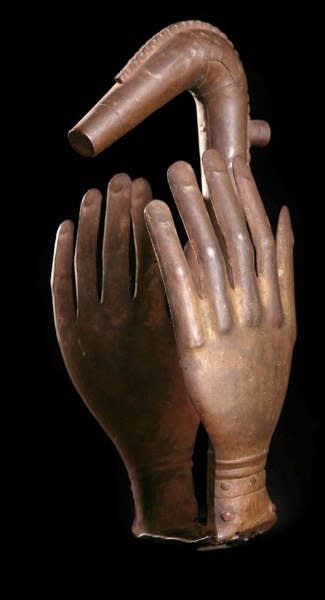

Jukun headdress, Nigeria. Height: 114,3 cm. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2015.445). Purchase, Pfeiffer, Leona Sobel Education, 2005 Benefit, and Dodge Funds; Gift of Dr. Mortimer D. Sackler, Theresa Sackler and Family; Andrea Bollt Bequest, in memory of Robert Bollt Sr. and Robert Bollt Jr.; Elaine Rosenberg, James J. Ross, and The Katcher Family Foundation Inc. Gifts, 2015.

Jukun headdress, Nigeria. Height: 114,3 cm. Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2015.445). Purchase, Pfeiffer, Leona Sobel Education, 2005 Benefit, and Dodge Funds; Gift of Dr. Mortimer D. Sackler, Theresa Sackler and Family; Andrea Bollt Bequest, in memory of Robert Bollt Sr. and Robert Bollt Jr.; Elaine Rosenberg, James J. Ross, and The Katcher Family Foundation Inc. Gifts, 2015. -

Image courtesy of Anita J. Glaze, 1969.

Image courtesy of Anita J. Glaze, 1969. -

-

Ikenga figure. Height: 73,5 cm. Image courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Ikenga figure. Height: 73,5 cm. Image courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art. -

-

-

-

Photo: Bruno Claessens. Image courtesy of the Blom Collection, Switzerland.

Photo: Bruno Claessens. Image courtesy of the Blom Collection, Switzerland. -

Image courtesy of the Fowler Museum at UCLA.

Image courtesy of the Fowler Museum at UCLA. -

-

-

-

-

Teke figure by the Master of the wedge-shaped beard. Image courtesy of Christie’s (11 December 2014, lot 52).

Teke figure by the Master of the wedge-shaped beard. Image courtesy of Christie’s (11 December 2014, lot 52). -

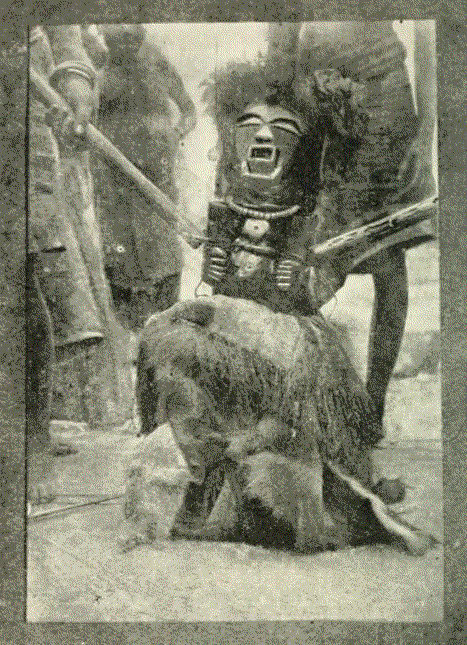

Ancestral figures from the shrine of the Basiatshiwa-Mwamuwa (Bahutshwe-Boyo). Chief Kimano II, Kabambare territory, Maniema. Photo by H. Goldstein, 1956. Published in Beaulieux (Dick), “Belgium collects African Art”, Brussels, 2000: p. 94.

Ancestral figures from the shrine of the Basiatshiwa-Mwamuwa (Bahutshwe-Boyo). Chief Kimano II, Kabambare territory, Maniema. Photo by H. Goldstein, 1956. Published in Beaulieux (Dick), “Belgium collects African Art”, Brussels, 2000: p. 94. -

Senufo ceremonial staff. Height: 90,5 cm. Photo by Ferry Herrebrugh. Image courtesy of Rutger & Irene der Kinderen, The Netherlands.

Senufo ceremonial staff. Height: 90,5 cm. Photo by Ferry Herrebrugh. Image courtesy of Rutger & Irene der Kinderen, The Netherlands. -

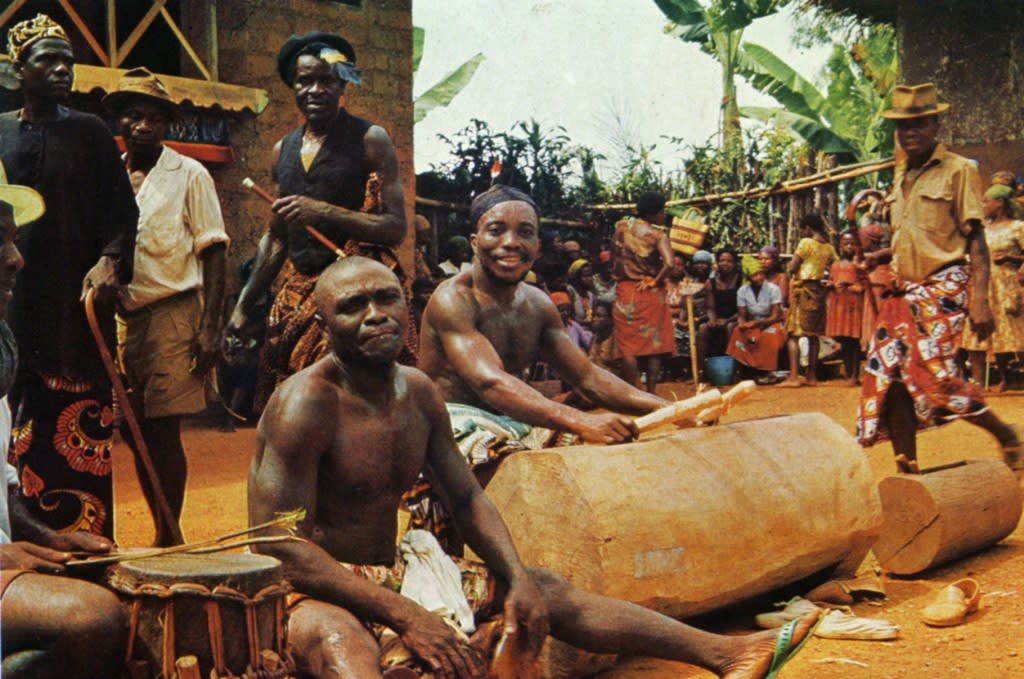

Atem trying out a new slit gong. Image courtesy of Brain & Pollock, 1971 (color plate 12).

Atem trying out a new slit gong. Image courtesy of Brain & Pollock, 1971 (color plate 12). -

Foyn Phuonchu Aseh of Babanki-Tungo in his workshop. Published in Emonts (J.), Ins Steppen und Bergland Innerkameruns. Aus dem Leben und Wirken deutscher Afrika Missionare, Aachen, 1927: p. 219.

Foyn Phuonchu Aseh of Babanki-Tungo in his workshop. Published in Emonts (J.), Ins Steppen und Bergland Innerkameruns. Aus dem Leben und Wirken deutscher Afrika Missionare, Aachen, 1927: p. 219. -

-

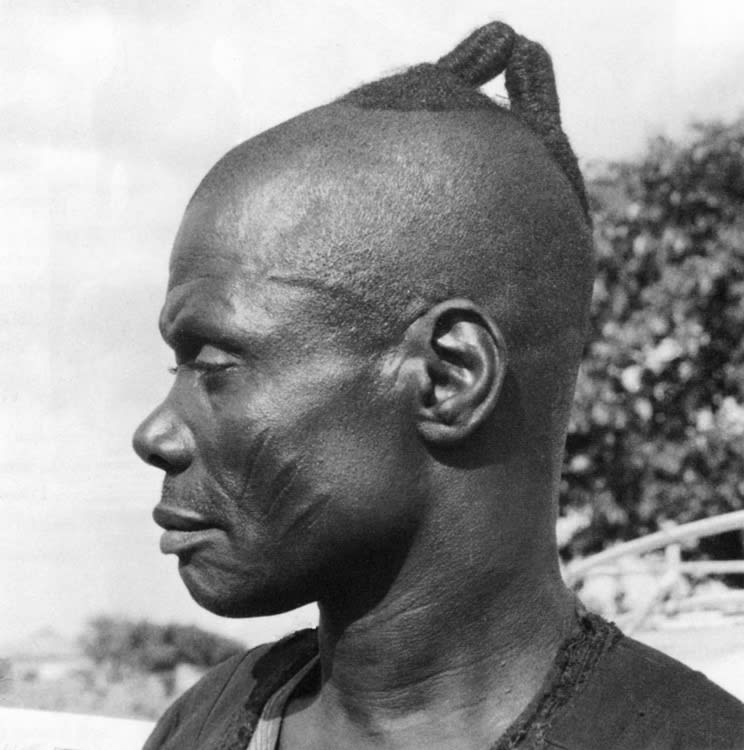

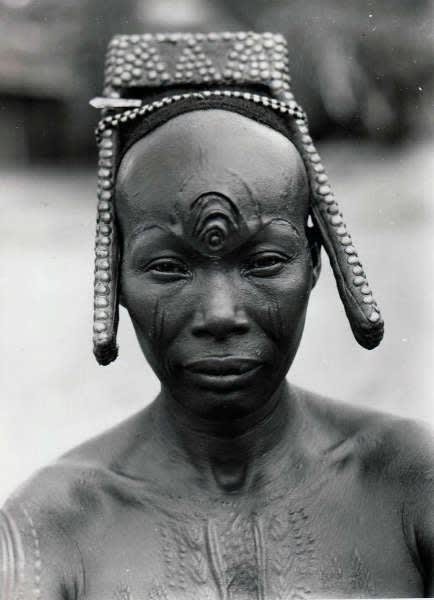

Kings’s messenger, “are”. Shaki. Photo by William Fagg, 1959.

Kings’s messenger, “are”. Shaki. Photo by William Fagg, 1959. -

Kran figure (Liberia). Height: 52,7 cm. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Kran figure (Liberia). Height: 52,7 cm. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s. -

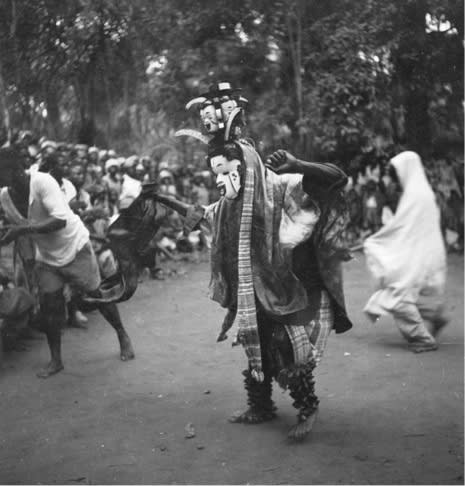

An okoroshi masquerade featuring the character of Onyejuwe. Photo by G. I. Jones, 1930s, at Eziama Orlu (Isuama Igbo).

An okoroshi masquerade featuring the character of Onyejuwe. Photo by G. I. Jones, 1930s, at Eziama Orlu (Isuama Igbo). -

Height: 76,8 cm. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Height: 76,8 cm. Image courtesy of Sotheby’s. -

-

Image courtesy of the Ethnologisches Museum (SMPK), Berlin, Germany (III.C.8206).

Image courtesy of the Ethnologisches Museum (SMPK), Berlin, Germany (III.C.8206). -

-

Keaka headdress. Image courtesy of the Linden Museum Stuttgart. Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde, Stuttgart, Germany (#45.455). Height: 22 cm.

Keaka headdress. Image courtesy of the Linden Museum Stuttgart. Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde, Stuttgart, Germany (#45.455). Height: 22 cm. -

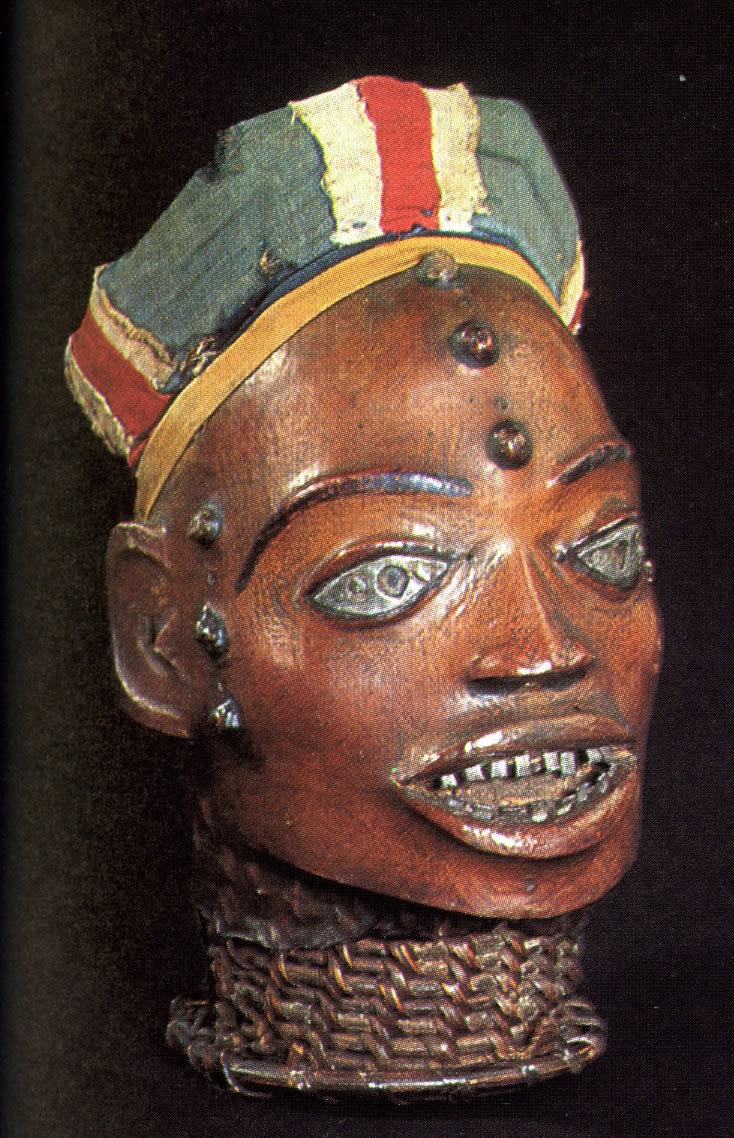

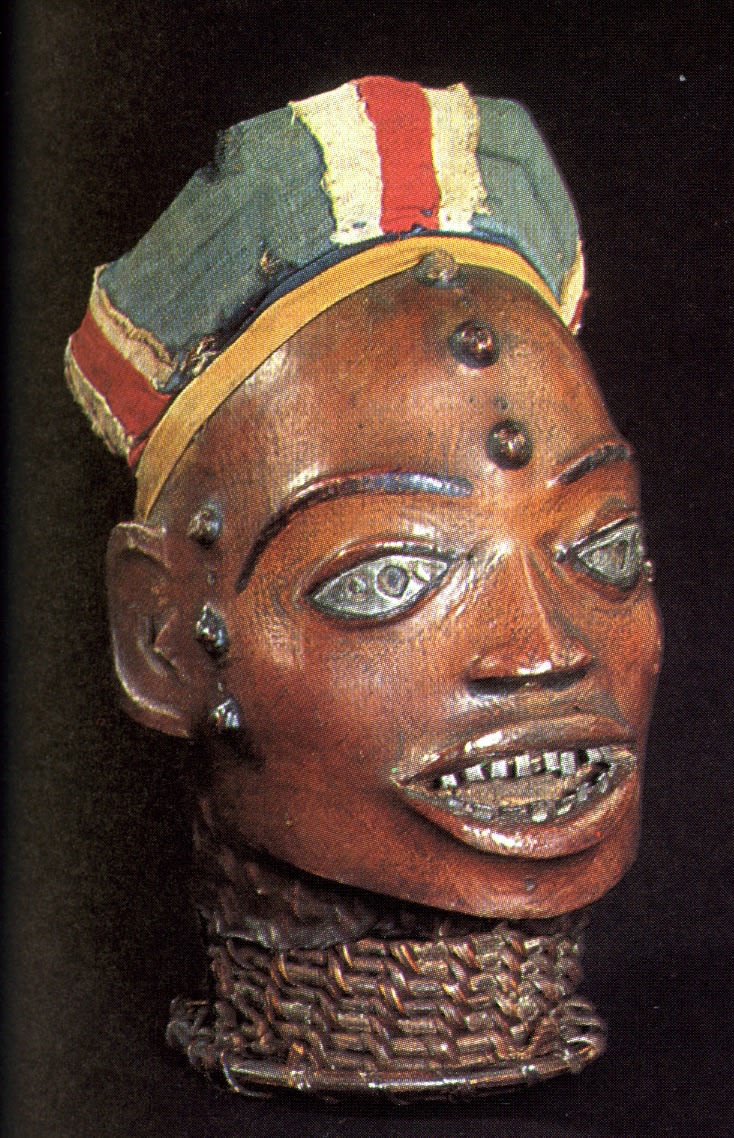

Keaka headdress. Image courtesy of the Linden Museum Stuttgart. Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde, Stuttgart, Germany (#45.455). Height: 22 cm.

Keaka headdress. Image courtesy of the Linden Museum Stuttgart. Staatliches Museum für Völkerkunde, Stuttgart, Germany (#45.455). Height: 22 cm. -

Vili drum. Height: 100,3 cm. Image courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum (#E6754).

Vili drum. Height: 100,3 cm. Image courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum (#E6754). -

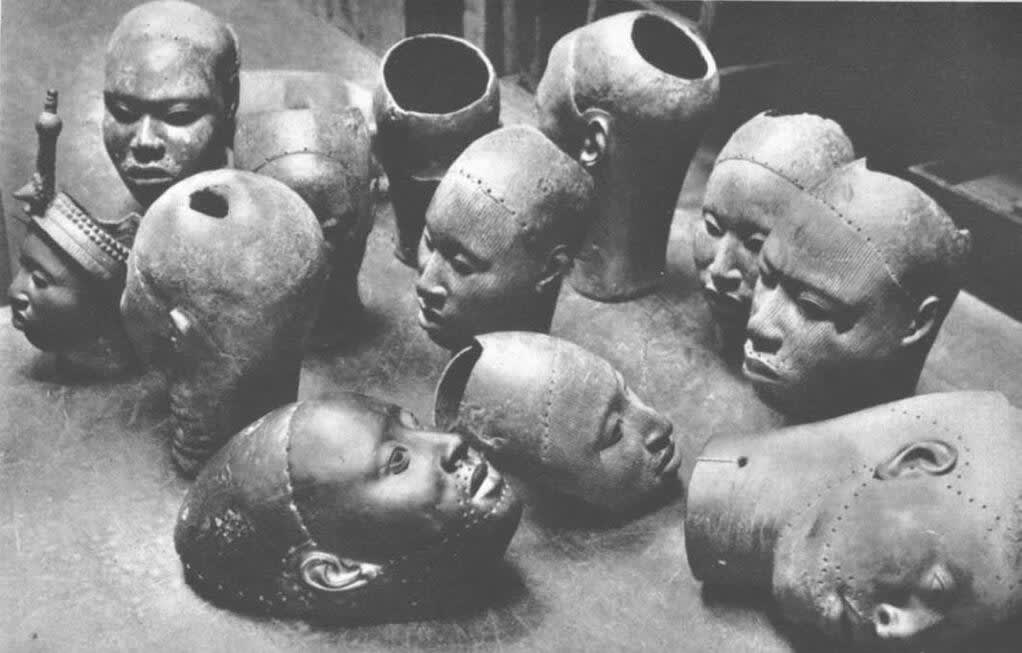

The Wunmonije heads at the British Museum in 1948. Published in Drewal (H.J.) & Schildkrout (E.), Dynasty and Divinity: Ife Art in Ancient Nigeria, 2009: p. 4, fig. 2

The Wunmonije heads at the British Museum in 1948. Published in Drewal (H.J.) & Schildkrout (E.), Dynasty and Divinity: Ife Art in Ancient Nigeria, 2009: p. 4, fig. 2 -

Mangbetu or Zande bark box. Height: 44,5 cm. Image courtesy of the Collection Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden, The Netherlands (#2668-24).

Mangbetu or Zande bark box. Height: 44,5 cm. Image courtesy of the Collection Museum Volkenkunde, Leiden, The Netherlands (#2668-24). -

-

-

Image courtesy of the Africarium collection.

Image courtesy of the Africarium collection. -

Boa figure. Height: ca. 50 cm.

Boa figure. Height: ca. 50 cm. -

-

-

-

Image courtesy of Tajan.

Image courtesy of Tajan. -

-

-

-

-

Image courtesy of Petra Schütz / Detlef Linse.

Image courtesy of Petra Schütz / Detlef Linse. -

Image courtesy of Boris Kegel-Konietzko, 1959.

Image courtesy of Boris Kegel-Konietzko, 1959. -

A Luba Shankadi mboko figure. Ca. 1930. Height: 59 cm.

A Luba Shankadi mboko figure. Ca. 1930. Height: 59 cm. -

Image courtesy of Zemanek-Münster.

Image courtesy of Zemanek-Münster. -

-

-

Angas figures. Height: 53,3 & 55,9 cm. Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, The de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA., USA (#1996.12.34.1 & 2).

Angas figures. Height: 53,3 & 55,9 cm. Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco, The de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA., USA (#1996.12.34.1 & 2). -

Image courtesy of Dorotheum.

Image courtesy of Dorotheum. -

Kotoko figure on horseback. Height: 4,8 cm.Image courtesy of Sotheby’s (Sotheby’s, New York, “Masterpieces of African Art from the Collection of the Late Werner Muensterberger “, 11 May 2012. Lot 58.).

Kotoko figure on horseback. Height: 4,8 cm.Image courtesy of Sotheby’s (Sotheby’s, New York, “Masterpieces of African Art from the Collection of the Late Werner Muensterberger “, 11 May 2012. Lot 58.). -

Thomas Ona (1938). Photo source unknown to me so any additional information is very welcome.

Thomas Ona (1938). Photo source unknown to me so any additional information is very welcome. -

Image courtesy of Artcurial.

Image courtesy of Artcurial. -

Image courtesy of Binoche et Giquello.

Image courtesy of Binoche et Giquello.