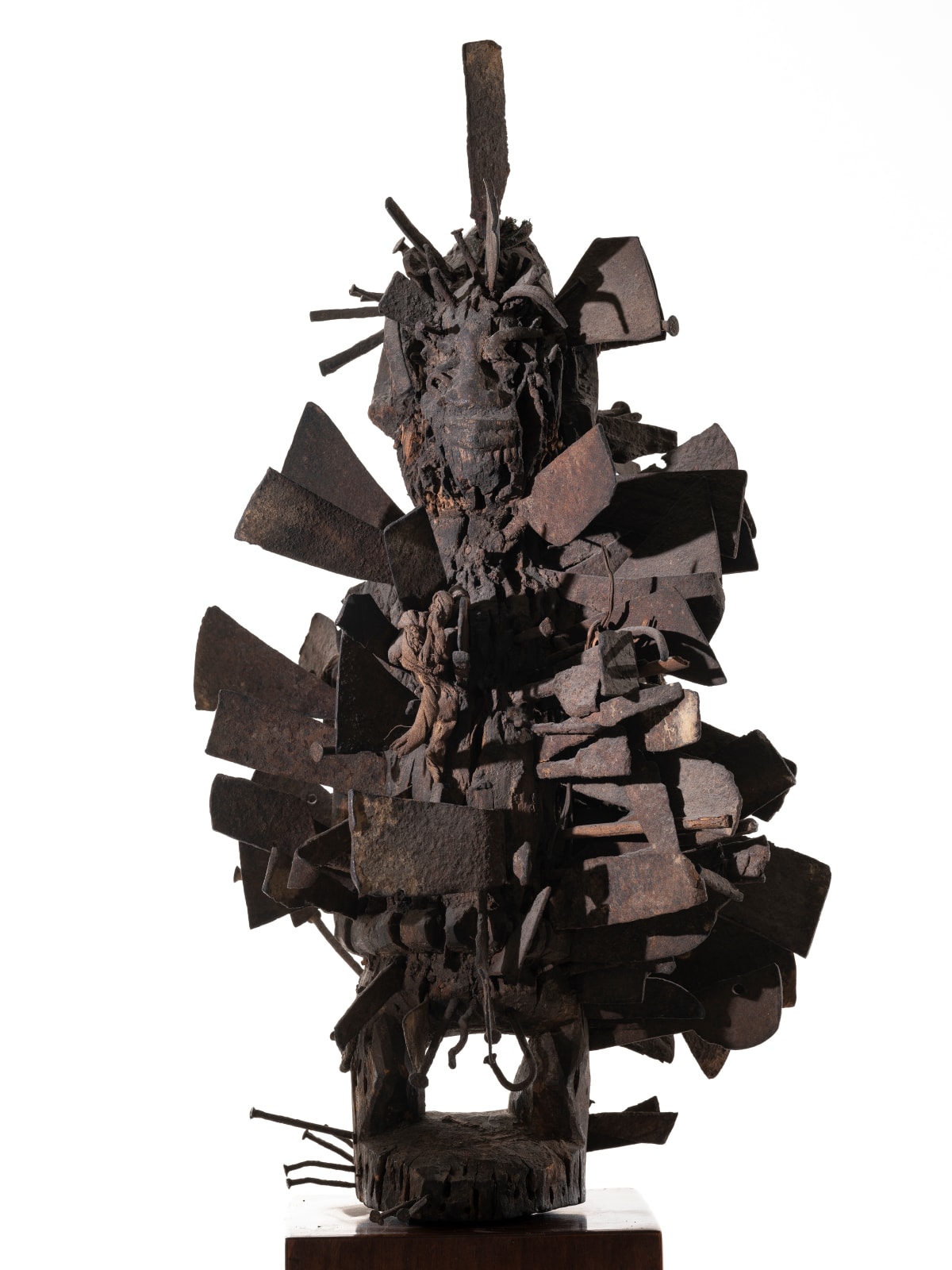

Anonymous Kongo artist (D.R. Congo)

origin: D.R. Congo - mid 19th century

17 3/4 x 9 7/8 x 8 5/8 in

Further images

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 1

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 2

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 3

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 4

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 5

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 6

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 7

)

-

(View a larger image of thumbnail 8

)

This awe-inspiring statue is known as a nkisi nkondi. The term nkisi has no equivalent in any Western language and should best remain untranslated. Its first and most straightforward meaning is that of a container. The term nkisi was not only given to the statue, but it also referred to the spirit it housed. Rather than representing this spiritual entity, a figurative wooden figure provided a vehicle for it.

However, the statue itself was not yet a nkisi, but only the home for one. It was only when a ritual specialist, known as nganga, activated the wooden figure, it would come to house a nkisi spirit. This power was put into the statue by the accruement of ritual ingredients known as bilongo. It was the responsibility of the nganga to customize it by adding symbolic materials and ritual substances to attract specific spirits to assist with a particular problem. While the basis material for a nkisi figure was wood, an activated figure would be an assemblage of heterogeneous objects and materials, continuously increasing while being ritually used. The bilongo were often packed in a cavity cut into the figure’s head or stomach. These ‘medicines’ were loaded with sacred power. They were often tightly wrapped in knots and nets to give visual expression to the idea of contained forces. The diverse ingredients of the medicines included special earths and stones, leaves and seeds, parts of animals, and feathers, and were specifically combined to attract and direct forces to a desired goal. Consequently, each nkisi was unique, and could be controlled only by the nganga that conceived its creation.

Nkisi are thus the product of the division of the working process between a sculptor and a ritual specialist. The original wooden figure left the carver’s hands in an unfinished stage. The nganga’s intervention was a ritual one, yet it fundamentally influenced the morphology of the figure and its artistic effect. The sculptor habitually anticipated the ritual activation of his figure. While he delicately finished the face, he did not sculpt the headdress itself. The sculptor often prepared a cylindrical structure on top of the head to accommodate and facilitate the attachment of a power charge. This headdress added by the nganga became an integral part of the figure, interacting with the carved face through its volumes, shapes, and textures. As can be observed on the present power statue, before being sold, nkisi were often desacralized, stripped of their bilongo, exposing a previous stage of non-finito of the statue.

As ritual experts, nganga were approached by clients to address any of a multitude of crises that could emerge in the community, including illness, and social strife. A nkisi was essentially a container of spiritual forces that were directed to investigate the underlying cause of a specific problem. Minkisi were essential to the nganga’s profession, creating a focal point from which to draw upon the spirit realm and its powers. Just as minkisi were directed toward specific ends, the nganga that owned and controlled them was specialized to address specific issues. There existed as many types of minkisi, as there were problems.

Only the most experienced nganga could assume the responsibility of important and powerful minkisi; those concerned with political matters and the administration of justice known as nkisi nkondi. These large minkisi had a communal function, in contrast to the smaller ones which were often devoted to more personal private ends. Such principal minkisi were used at the hearings of law cases, acting as a kind of detective who could prove the accused person’s guilt, but also as the guardian of public safety, morality, and social order. It was both a policeman who preserved public order, and an executioner who punished offenders. On special occasions this type of nkisi nkondi was brought outside in a public setting where judicial procedures took place. The parties involved came before the figure with the nganga, and together they investigated the problem at hand. When an agreement was to be made, representatives from both parties took an oath in front of the nkisi nkondi. The oath was then sealed by driving a nail or other sharp metal object into the figure to activate its power. According to some sources each party first licked the nail, to render the agreement binding, and by this means informing the nkondi of the identities of those for whom it was supposed to act. The nkisi swore to observe the engagement and punish anyone breaking the treaty.

An elementary characteristic of nkisi nkondi is the large number of bits of metal driven into the figure to activate the spirit it contained. Consequently, this type of power statue is often called a ‘nail figure’. Nails and metal wedges have been inserted all over the figure’s body. The torso is the usual place for nails because problems were felt in the chest, around the heart. The head, hands, legs and feet are usually kept relatively free of nails. The large quantity of nails driven into the figure shows that this was an important power statue. It was probably frequently used for very significant matters. Each of the nails driven into the figure represents the taking of an oath, the witnessing of an agreement, or some other occasion when the power of the figure was invoked. Beside the head, the statue’s belly was another spiritual focal point, usually packed with ritually charged substances and then sealed with resin and a mirror.

This magnificent statue can be attributed to the Dondo, one of the Northeastern Kongo groups. Its style is one of the more realistic of the Lower Congo regio, characterized by a rounded head and big eyes covered with pieces of metal. Unlike the decorative round-headed nails which occur in Songye statuary, the metal wedges on the nkondi figures are far more heterogenous in nature. The multitude of origins of these wounding instruments indicates a long ritual life.

Provenance

Mario Carrieri, Milan, Italy

Joris Visser, Brussels, Belgium

Private Collection